Volume 15:4, Fall 2014

A Splendid Wake Issue

William Stafford served a term as US Poet Laureate from 1970 to 1971, the first Midwestern native and the first West Coast resident to be so honored. According to Poetrys Catbird Seat: The Consultantship in Poetry in the English Language at the Library of Congress, 1937-1987 by William McGuire: when the Library of Congress offer came through for certain, his wife Dorothy, also a teacher, four children, and Stafford took a poll. The vote for Washington, DC included only one nay, which was Staffords; he knew hed miss the openness of life in Oregon, the country roads he could cycle to work on. The Staffords, fortunately, found a house to rent in the woodsy Virginia country near McLean.

In addition to accepting reading and lecture gigs around the country, in and around Washington, Staffords calendar was full. At a meeting of the District of Columbia Commission on the Arts he got to know May Miller Sullivan, the doyenne of the citys black poets, and took part in poetry workshop gatherings at her apartment.”

Stafford also quickly became close friends with Myra Sklarew, Linda Pastan, and Ann Darr, and those friendships continued to grow over many years. He joined the poetry workshop that took place at Siv Cedering Fox‘s house whenever he was in DC. And Myra reports: “He led many workshops with my students at American University. He’d come and be in residence and work patiently with them over many days.”

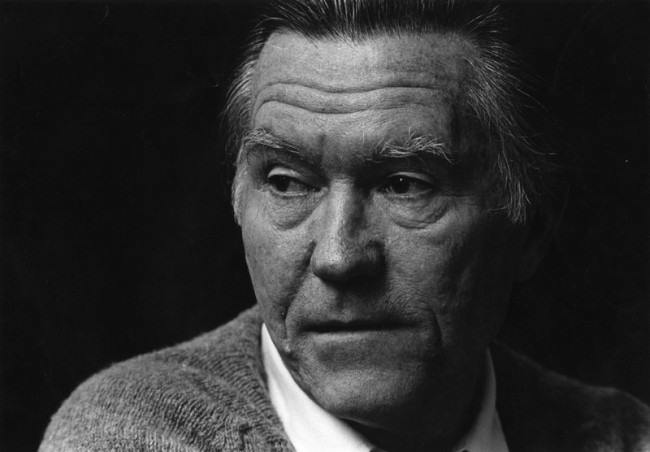

William Stafford

How to bring Bill Stafford here among us, to let those who never met him know him, and to help those who did know him remember him? More than anyone I can think of, he changed us by our knowing him. In the end, we have that. And his voice. In his words. In his poetry, above all.

Photo: William Stafford Archives, Courtesy of Lewis & Clark College Aubrey Watzek Library Archives & Special Collections.

Every time I thought up some new program at American University, I would call Bill and ask him to cometo lead a workshop, give a reading, talk to students, to recommend writers. I think he visited every town in America. He really knew our country. And he knew the countrys poets, even if they werent known widely outside of their towns.

Bill was born in Hutchinson, Kansas in 1914. He worked as a laborer in sugar beet fields, on construction jobs and in an oil refinery during his schooling years. During World War II, he was a conscientious objector, and during that time he worked in Forest Service and Soil Conservation while he lived in CO camps for four years. I asked him when he decided to take a different path from the country. There was tremendous patriotism during that war; it was no easy thing to decide not to take part. His answer: I didnt change; the world did. By the way, he wrote to me in 1980, the Trocmés were models for us, back in the 40’s, and I remember much written about them in Fellowship Magazine, the publication of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, which was jumping in those days, with various champions like Martin Luther King and Bayard Rustin. Pastor André Trocmé, the Lutheran pastor of Le Chambon, France, his family and the all the inhabitants of their town, were responsible for saving several thousand Jews during the War. Every single family took in people, hid them and cared for them.

Bill taught us about being willing to fail… I am following a process that leads so wildly and originally into new territory that no judgment can at the moment be made about values, significance…Now I am headlong to discover.

In his book of essays and reviews, Writing the Australian Crawl, Bill wrote: A writer is not so much someone who has something to say as he is someone who has found a process that will bring about new things he would not have thought of if he had not started to say them. That is, he does not draw on a reservoir; instead, he engages in an activity that brings to him a whole succession of unforeseen stories, poems, essays, plays, laws, philosophies, religions, or…

I always thought of him as our Zen poet. If there were times we could not hear him, it was because we were not being quiet enough.

When he would start to read his poems, he simply veered off from talking. It happened so quickly you couldnt tell when you had entered the deeps of his poems; you could only register that you were suddenly there.

Bill said there was no such thing as writers block: you just lower your standards and keep on going.

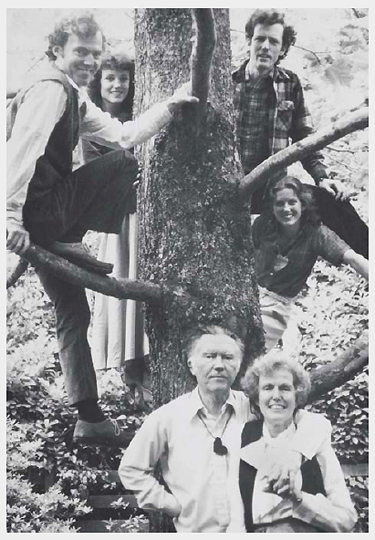

The Stafford “family tree”: from left to right, in the branches: Bret, Kit, Kim and Barbara. On the ground: William Stafford and wife Dorothy. Photo: William Stafford Archive, Courtesy of Lewis & Clark College Aubrey Watzek Library Archives & Special Collections..

I asked him once what would happen to him if he were separated from those he loved: I would grow colder. Like a planet turning in space. And what, I asked him, when he had to drive his wife Dorothy 150 miles out of Sisters Canyon when she became suddenly ill, did you think of as you were driving? I tried to drive as well as I ever had. I thought of steering carefully.

Dorothy wrote in a letter to me after their son Bret died: We went up, my daughter and I, into the canyon and there we found forget-me-nots everywhere, and we wrote Brets name into the lichens on the rocks in spring.

Bill sent me a poem after my father died. We had talked about the way we want to stay with them and the way the world and our life calls us back.

Doing the Needful

Carrying you, a little model carefully dressed

up, nestled on velvet in a tiny box,

I climb a mountain west of Cody. Often,

cut by snow, sheltering to get warm, I take

you out and prop you on the rocks, looking south

each time. You can see the breaks, down through cedars

to miles of tan grass. I put you back in the box

and hold you inside my coat. At the top I put you

wedged in a line of boulders, out of the wind.

It is very late by now, getting dark. I leave

you there. All the way down I can hear the earth

explaining necessity and how cold it is when you walk

away, even though youve done all you can.

Dorothy Stafford wrote in April 1994: On Friday Bill and I would have been married 50 years. I wrote him a long letter about the joys and sorrows of those years, about how lucky I was to have been a partner of one so kind, intelligent, wise, funny, original and dear, ‘the golden string’ he followed led me too into those secret places of light and discovery.

Bills son Kim Stafford wrote: “There was this reporter trying to get at Bills grief after his friend Richard Hugo died. After a significant pause, Bill said: ‘We were on a cash basis. No debts. No charges.'”

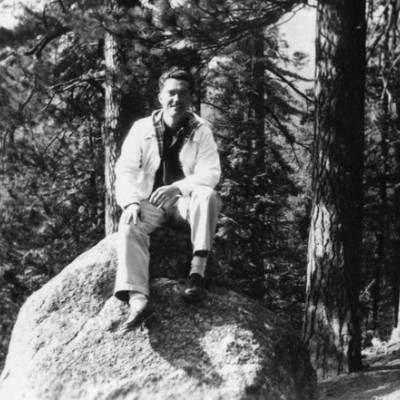

Photo: William Stafford Archive, Courtesy of Lewis & Clark College Aubrey Watzek Library Archives & Special Collections..

Bill gave a reading sponsored by Rod Jellema at the University of Maryland in April 1980. He said: Something I wrote down, something our daughter Kit said. Ever since this happened, I saved it, as the way to do it. Our family had been out at the coast, in Oregon, hiking around all day, everyone was tired and sleepy. Time to go home. I had to drive back over the coast range. So Kit, 6 years old, stood by the dashboard to help Daddy drive, that is, she was going to talk to keep me awake. She began to imagine a way of life for the two of us. And this is what she said: We have an old car. The kind that gets flat tires. But inside would be wolfskin on the seats and warm fur on the steering wheel, and wolf fur on all the buttons. And wed live in a ranch house made out of logs with a loft where youd sleep. Youd walk a little ways and thered be the farm with the horses. Wed drive to town and wed have flat tires. And be sort of…old. She didnt need to know…how. She just needed to trust her own life going along, and I always think she could be psychoanalyzed for all that wolf fur inside the car.

Our only famous relative, Bill said in an interview in 1975 in Poetry Now, was Robert Ingersoll, the orator and atheist, who used to stand before a crowd and say, If God exists Ill give Him five seconds to strike me dead with lightning. Hed take out his watch and look at itfive seconds would go byand the crowd would be astounded, expecting it to happen. In those days you didnt do things like that…I used to think Ingersoll was just luckyGod was looking somewhere else. Ingersoll became a Civil War hero. Ingersoll was also the person who delivered the eulogy for Walt Whitman at his funeral.

Bill remembers being read to constantly by his mother and father. All that reading had an impact on me. In fact, writing was sort of the exhale part of inhale reading. Id write things in grade school, then come home and publish them to my parents. Theyd say, You know, Billy, thats nicethats the Pulitzer Prize for our block.

By the time Bill reached college, he knew he wanted to be a poet. I dont think of it as an ambition, exactly. If one is ambitious to be a poet, hes ambitious to be poor and unrecognized and unknown.

Poet Louis Simpson said of Bill: If ever this country is to have a sense of itself, it will be through work like Staffords.

But let the last word be Bills. His son Kim Stafford sent what Bill called his Informal Will to us after Bills death. It was written in August 1964, twenty-nine years before Bills death.

It has long been my desire that when my time comes to die, I may be enabled to sneak out of the world….If it should happen that dying would give me time for volition, I would like to disappearjust take my body along somewhere and let it be lost along with myself. My reason would be simply that such disappearance would be most convenient for everyone….Those whom my limitations, inattention, forgetfulness made endure a waste of their time, and those who suffered my repeated banalitiesI ask that they forgive me…And those I helped, too…may they forgive me, all of them often terribly dear in my sight, but sometimes, too, simply neglected, or swimming deep in my inattention, like a dream.

The will ends this way: Signed this 20th day of August 1964, not in the presence of witnesses, but in the ease and quiet of my study on this calm summer day.

Sources

William McGuire, Poetrys Catbird Seat: The Consultantship in Poetry in the English Language at the Library of Congress, 1937-1987, Library of Congress, 1988

Kim Stafford, Early Morning: Remembering My Father, William Stafford, Graywolf Press, 2003

William Stafford, Writing the Australian Crawl: Views on the Writer’s Vocation, University of Michigan Press, 1978

William Stafford, Crossing Unmarked Snow: Further Views on the Writer’s Vocation, University of Michigan Press, 1998

William Stafford (edited by Kim Stafford), Ask Me: 100 Essential Poems of William Stafford, Graywolf Press, 2013

Myra Sklarew was educated at Tufts University and the Writing Seminars at Johns Hopkins University. She studied at Cold Spring Harbor Biological Laboratory with Salvador Luria and Max Delbruck and conducted research in frontal lobe function of Rhesus monkeys at Yale University School of Medicine. She is the author of 17 collections of poetry, fiction and essays including Invitation to a Country Called Aging (co-written with Patricia Garfinkel, Politics & Prose Books, 2018), Harmless (Mayapple Press, 2010), The Witness Trees (Cornwall Books U.S./London/Dora Teitelboim Center for Yiddish Culture, 2000, reprinted 2007), Lithuania: New & Selected Poems (Azul Editions, 1995), and the forthcoming A Survivor Named Trauma: Holocaust Memory in Lithuania (SUNY University Press). Awards include the PEN Syndicated Fiction Award and the National Jewish Book Council Award in Poetry for From the Backyard of the Diaspora (Dryad Press, 1981). She is the former president of the Yaddo Artist Community and professor emerita in the Department of Literature, American University. To read more by this author: Five poems, Winter 2004, Whitman Issue, Myra Sklarew on May Miller: Memorial Issue, and Myra Sklarew on Leon-Gontran Damas: Forebears Issue