So what is a Gertrude Stein aficionado doing writing about Archibald MacLeish? The two poets would seem very different: she an experimenter, he a formalist; she a Harvard grad, he a Yalie (though MacLeish also graduated from Harvard law school at the top of his class), she with her limited public service activities, he a statesman, government leader, and soldier.

I attribute my interest in MacLeish to serendipity, curiosity, and a willingness to challenge myself by exploring the work of a poet I believe few would be interested in reading today. The day MacLeish died, I wandered into Bridge Street Books in Georgetown and purchased a copy of his verse play J.B., winner of one of three of MacLeish’s Pulitzer Prizes. (How is it possible that a poet wins three Pulitzer Prizes and is not read any more? More on this below.) Thinking I would read the play later, I put the book into my collection of poetry and it sat for 20 years, until serendipitously Kim Roberts asked me if I could write about MacLeish for this special edition of Beltway Poetry. I figured it was time for me to act on my original impulse to know something about MacLeish, with whom I share the same birthday, and so I raided the shelves of McKeldin Library at my alma mater, the University of Maryland.

Paris in the 1920s

I found the story of MacLeish’s life engrossing and covering some of the same territory as the life of Gertrude Stein. In fact, MacLeish became a neighbor of Stein’s in 1923 when he turned down an offer to become a partner in a prestigious Boston, Massachusetts, law firm. He had decided to pursue his writing in Paris. (Here’s a point in common with Stein who threw over a career in medicine and moved to Paris to become a writer.) I can imagine Archibald MacLeish strolling through Luxembourg Gardens in 1923 with his wife Ada, his six-year-old son Kenny, and one-year-old daughter Mimi, while Gertrude and her partner Alice B. Toklas were out walking their large white poodle.

Washington, DC in the 1940s

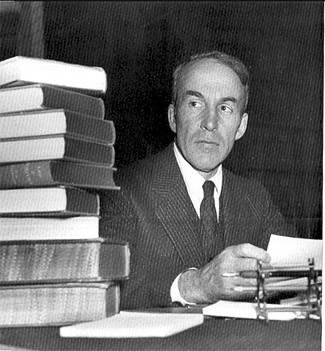

MacLeish in 1939, taken on the first day of his job as Librarian of Congress. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

MacLeish lived in the Capital for over ten years, beginning in 1939, during which time he held a number of influential political appointments. In addition to being Librarian of Congress, MacLeish served in the Office of Facts and Figures and the Office of War Information during World War II, and also wrote speeches for President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He was Assistant Secretary of State for Cultural and Political Affairs and, subsequently, Chief of the U.S. delegation to the organizing conference of UNESCO. MacLeish lived in Georgetown with his wife Ada and their children at 1520 33rd Street, between P and Volta Place. He left DC in 1949 to accept a teaching post at Harvard University.

A Sample of MacLeish’s Poetry

If few readers of poetry enjoy the work of Gertrude Stein, which is characterized by repetition, lack of usual punctuation, odd turns of phrase, and lack of everyday logic, to what does one attribute lack of readership for Archibald MacLeish‘s work? Before I answer that and prejudice the reader, I offer one of his best loved and much anthologized poems–one that critics point to as his best work. It depicts territory that most Americans are now more familiar with than they would like to be.

You, Andrew Marvell

And here face down beneath the sun

And here upon earth’s noonward height

To feel the always coming on

The always rising of the night:

To feel creep up the curving east

The earthy chill of dusk and slow

Upon those under lands the vast

And ever climbing shadow grow

And strange at Ecbatan the trees

Take leaf by leaf the evening strange

The flooding dark about their knees

The mountains over Persia change

And now at Kermanshah the gate

Dark empty and the withered grass

And through the twilight now the late

Few travelers in the westward pass

And Baghdad darken and the bridge

Across the silent river gone

And through Arabia the edge

Of evening widen and steal on

And deepen on Palmyra’s street

The wheel rut in the ruined stone

And Lebanon fade out and Crete

High through the clouds and overblown

And over Sicily the air

Still flashing with the landward gulls

And loom and slowly disappear

The sails above the shadowy hulls

And Spain go under and the shore

Of Africa the gilded sand

And evening vanish and no more

The low pale light across that land

Nor now the long light on the sea:

And here face downward in the sun

To feel how swift how secretly

The shadow of the night comes on . . .

The title “You, Andrew Marvell” refers to Andrew Marvell‘s 1650 poem “To His Coy Mistress.” The two poems share a common theme: time acting on man’s mortality. “You, Andrew Marvell,” written after MacLeish’s politically instigated trip to Persia in 1926, carries the burden MacLeish faced when he returned from his adventure to learn his aging father Andrew was seriously ill. (MacLeish was invited by the League of Nations to help evaluate the opium production problem in Persia, now known as Iran. MacLeish’s report concerning how to counter the opium trade provided recommendations to build a railroad along a specific route, which the League of Nations followed. )

The poem is written in four-line stanzas, except for the last two stanzas, where MacLeish allows a one-line stanza followed by a three-line stanza, and is written with consistent eight syllables to the line in an ABAB rhyme scheme. What distracts me first about this poem is the proliferation of filler words used to maintain the eight-syllables-to-the-line measure (e.g. and here, always, and). Yes, I know he is using the words to make this a one-sentence poem. Next, I am annoyed by the odd syntax that perhaps is forced by the ABAB rhyme format but also harkens back to how poems used to be written. (For example, in stanza three, line two, “the evening strange” may not mean “the strange evening” but may be an old poetic device that reiterates the first use of the word strange, which appears in line one of that stanza.)

A bigger problem for me with this poem is the lack of a breathing human being. Who is face down? Why should I care? MacLeish liked working with universality and he hoped to contain extraneous emotionalism. He relies heavily on Marvell’s poem to carry the message about the imminence of death—which, by the way, Marvell says we should counter now by intercourse with the coy mistress. In Marvell’s poem, I find human juice.

I know contemporary writers who will disagree with me about what I dislike in this poem. Perhaps this means that some time in the future MacLeish’s poetry will enjoy a revival.

Influence of the High Modernists

Among his contemporaries, the poets MacLeish most admired were T.S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. In December 1926, MacLeish wrote a letter to Pound that shows he was willing to hear criticism and to keep evolving. Pound had said MacLeish’s poems contained a marked influence of not only E.P. (Ezra Pound) but also T.S.E. (T.S. Eliot), G.S. (Gertrude Stein), and J.J. (James Joyce) and that MacLeish had not found his own voice. MacLeish answered:

I have never read G. S. except in advertised patches. But that doesn’t touch your real point. And there I am forced—with considerably more pain than you might imagine—to agree that you are right. I started to learn to write pretty late, having played with verse through a couple of years of the War and a law practice of three years so when I finally started I found myself with a lot of accepted ideas which tied me hand & foot. Then I began to discover that there were some who had been that way before me and who had gotten out. Chiefly you. Later Eliot.

Although E.P. advanced many literary careers, being Pounded by Ezra was pro forma for most writers who dared to show their work to him. However, critical reviews of MacLeish’s work often said his poetry was derivative of Pound and Eliot (in 1928, Conrad Aiken in reviewing The Hamlet of A. MacLeish said MacLeish remained “a slave of tradition, unable to throw off the influence of T.S. Eliot“). Current summaries about MacLeish still voice the same criticism.

Musings on the Pulitzer Prize

Despite this kind of criticism, MacLeish was selected three times to win a Pulitzer Prize. A prominent New York poet and literary careerist suggested to me that the Pulitzer Prize for poetry has often been given to poets of little consequence. I decided to have a look at who has won over the years. Here’s what I found:

—The prize has been awarded annually since 1922, with the exception of 1946;

—Of the 81 winners, including the winner for 2003, I never heard of eleven. Most of the unknowns (at least unknown to me) occur from 1927 to 1941 (such poets as Leonora Speyer, George Dillon, Audrey Wurdemann, Marya Zaturenska);

—Multiple Pulitzers were given to such poets as Edwin Arlington Robinson, Robert Frost, Stephen Vincent Benét, and Robert Lowell;

—Most of the deceased poets who got awards are well known for their contribution to American literature (such poets as Wallace Stevens, Marianne Moore, Elizabeth Bishop, Howard Nemerov, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Theodore Roethke);

—Pulitzers in the last thirty years have been given to poets prominently working in the American literary scene, including such poets as W.S. Merwin, Gary Snyder, John Ashbery, Washington’s own Henry Taylor, Charles Simic, and more recently Yusef Komunyakaa, Jorie Graham, and Paul Muldoon;

—The prize is now worth $10,000 but during MacLeish’s time it was more like $1,000. So winning a Pulitzer is more about status than financial reward.

The Pulitzer Prize is administered by Columbia University in New York City. The governing board seems to be predominantly newspaper people. I kept asking people who might have had some contact with MacLeish, did MacLeish get this prize because he was part of the old boy’s network? After all, he worked as a journalist for Fortune magazine and had close ties to Henry Luce. I found a letter from MacLeish written around January 1934 to his Houghton Mifflin editor Robert N. Linscott. The letter talks about MacLeish’s 1933 Pulitzer and refers to some criticism he had received from Conrad Aiken:

I don’t know why Aiken dislikes me. That’s between him and his typewriter. All I can say is that he is a fine poet & I’d like his good opinion & regret not having it.

Because I haven’t read anything written about myself for five years (a few exceptions for the comments of people who knew what they were saying) I have no idea what my “fame” is. I don’t know whether, Pulitzer Prizes altogether aside where they ought to be, I am considered one of the good American poets or not—nor who so thinks me. But I am quite sure that if I have been so placed it lies in the power of the termite army of critics to bring me damn well down. And I am also quite certain they will do it if they can I won’t pretend I am superior to it for one minute. I have a passion for fame. And I am very doubtful as to the extent to which my work really deserves to enjoy it.

All I can conclude is that Archibald MacLeish got his Pulitzer Prizes in the same manner every other writer got his or hers. I found no evidence to suggest any favoritism. Although there may be some Pulitzer Prize winners whose work I don’t care for and I wonder how they got such an award, in most cases the writer was prominent at the time of his or her selection. I also note that Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot never won a Pulitzer.

The Enormity of MacLeish’s Accomplishments

The scope of this essay does not allow me to discuss everything Archibald MacLeish accomplished and how those aspects of his life dovetailed with his publication record. So I offer this time line depicting some of the highlights of his remarkable working life and some of his many publications.

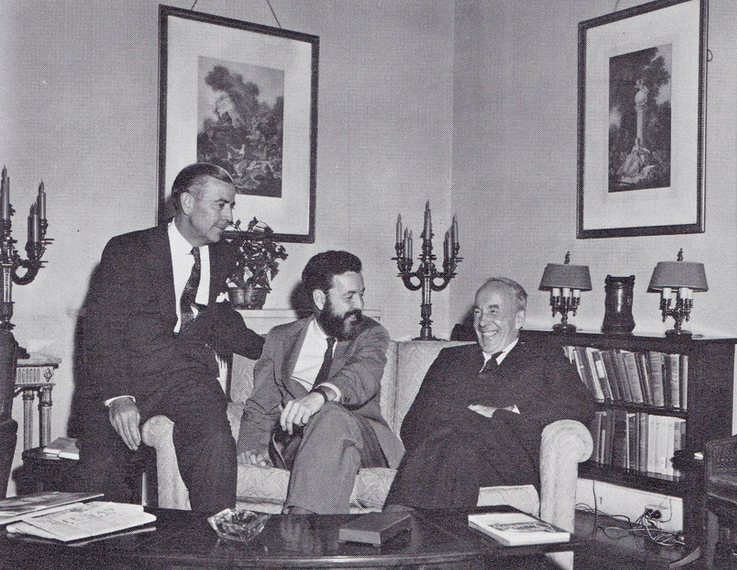

Quincy Mumford, Randall Jarrell, and Archibald MacLeish in the Poetry Office, Fall 1956. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Archibald MacLeish Time Line

1892 ………(May 7) Born, Glencoe, IL

1915 ………Graduated Yale

1916 ………Married Ada Taylor Hitchcock, an accomplished classical music singer who studied with Nadia Boulanger

1917-18 ….WW I US Army service in artillery unit in France

1919 ………LL.B, Harvard

1919-21 …Taught law in Harvard’s Government Department & was an editor for The New Republic

1921-23 …Practiced law in Boston firm of Choate, Hall and Stewart

1923-28 …Lived and wrote poetry in France

1924 ………The Happy Marriage (poetry)

1925 ………The Pot of Earth (poetry)

1926 ………Nobodaddy (play)

1928 ………The Hamlet of A. MacLeish (poetry)

1928-29 …Traveled through Mexico on foot and mule back retracing the route of Cortez

1929-38 …Served on editorial board of Fortune magazine

1930 ………New Found Land (poetry)

1932 ………Conquistador (poetry)

1933 ………Frescoes for Mr. Rockefeller’s City (poetry)

1933 ………Pulitzer Prize for Conquistador

1935 ………Panic (play)

1937 ………The Fall of the City (verse play for radio)

1938 ………Air Raid (play)

1939 ………America Was Promises (poetry)

1938 ………Developed Nieman Graduate Program for Journalists at Harvard

1939-44 …Librarian of Congress

1940 ………The Irresponsibles (prose)

1941-42 …Director, U.S. Office of Facts and Figures

1942-43 …Assistant Director of U.S. War Information

1944-45 …Undersecretary of State

1946 ………UNESCO development work and leadership

1948 ………Actfive and Other Poems (poetry)

1949-62 …Boylston professor of rhetoric at Harvard

1952 ………Collected Poems 1917-1952 (poetry)

1952 ………The Trojan Horse (play)

1953 ………Pulitzer Prize for Collected Poems 1917-1952

1953 ………National Book Award in poetry

1953 ………Bollingen Prize for poetry

1953-56 …President of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

1955-58 …Worked to free Ezra Pound from St. Elizabeths Hospital, where he was incarcerated

1958 ………J. B. (verse play produced on Broadway)

1958 ………Pulitzer Prize for J.B.

1961 ………Poetry and Experience (prose)

1966 ………Academy Award for motion picture The Eleanor Roosevelt Story

1967 ………Herakles (play)

1968 ………The Wild Wicked Old Man (poetry)

1971 ………Scratch (play)

1972 ………The Human Season (poetry)

1977 ………Presidential Medal of Freedom

1977 ………Cosmos Club Award

1978 ………Riders on the Earth (prose)

1985 ………Collected Poems, 1917-1982 (poetry)

1982 ………(April 20) Died, Boston

MacLeish as a Celebrated Librarian of Congress

MacLeish made major contributions to the literary life in the nation’s capital that radiate through the years to our time. As Librarian of Congress, he not only did major restructuring of that organization, making a difference in whether any writer could effectively use the Congressional library, but he also set the path for recognition of poets by establishing how the Consultant in Poetry position would work. Eventually that consultancy would become Poet Laureate of the United States.

MacLeish was recruited for the Librarian of Congress job first by Justice Felix Frankfurter, who had been one of MacLeish’s Harvard Law School professors and a continuing friend and colleague through the years. MacLeish declined because he wanted to devote himself again to creative writing. Nevertheless he was invited by Franklin Delano Roosevelt to lunch, and MacLeish reported: “Mr. Roosevelt decided that I wanted to be librarian of Congress.” Getting congressional confirmation was not easy because MacLeish had no experience for such a job, but the annals of the Library of Congress praise him as one of the great and significant heads of this important institution.

MacLeish Established Path to U.S. Poet Laureateship

In 1937, a shipbuilder named Archer M. Huntington donated money to the Library of Congress to establish the Consultancy in Poetry. Huntington’s choice for the position was Joseph Auslander, who MacLeish had described in a 1926 letter to Pound as a “word fellow with the digital dexterity of a masturbating monkey and as little fecundity.” Although Auslander attracted noted poets such as Robinson Jeffers, Robert Frost, Carl Sandburg, and Stephen Vincent Benét to the Library for readings, MacLeish was determined to replace him and establish the position as a rotating post, not a lifetime entitlement. Getting a prominent poet to accept the consultancy took MacLeish until July 1943, when Allen Tate accepted the position. More interesting was MacLeish’s third consultant, Louise Bogan, who was a long time antagonistic critic of MacLeish. At the cocktail party he organized in her honor in 1944, she asked why he appointed her. Because she was the best person for the job, MacLeish replied.

Dealing with People and Politics

Dealing with difficult people was a skill MacLeish had developed throughout his life. Just as Gertrude Stein discarded friends, so did her one-time friend Ernest Hemingway. In the summer of 1924, MacLeish met Hemingway indirectly through Sylvia Beach, owner of the Paris bookstore Shakespeare and Company. After reading Vignettes in Our Time, MacLeish sought out the author. For a short period after they became acquainted, they were sparring partners, but MacLeish, who was seven years older than Hemingway, took too many batterings from Pappy, the nickname MacLeish called his younger friend (documented in 1927 letters from MacLeish to Hemingway) and which became Papa to fans of Hemingway. It was Hemingway who got MacLeish to help extricate Pound from St. Elizabeths mental institution where Pound had been imprisoned after World War II for treason.

I stumbled upon a couple of people who had close up encounters with MacLeish. William Heyen said MacLeish insisted he should call him Archie. Bill was a young man at the time so this felt like a breach of decorum. My scene4.com editor/publisher Arthur Meiselman worked on the Broadway production of MacLeish’s play J.B., directed by the renowned Elia Kazan. Arthur found MacLeish alternating between mellow and stiff. Both Arthur and Archie hated Kazan, who—according to Meiselman—gave J.B. strange Brechtian details. While admitting that leading actors Raymond Massey and Christopher Plummer made J.B. “somewhat compelling,” Meiselman found MacLeish “a mediocre dramatist (as opposed to ‘playwright’)” and said the play “simply doesn’t make us care.” Nonetheless J.B. won a Pulitzer Prize and the Tony Award, with Kazan taking recognition as best director. Washington poet and playwright Grace Cavalieri said this was the play and production that inspired her to start writing for theater.

One other aspect of MacLeish’s life that should be mentioned is that he became a socially aware and politically oriented writer in the 1930s. He overthrew the philosophy of his own poem “Ars Poetica” by refuting art for art’s sake and challenging writers to speak out against tyranny, particularly Fascism. Later he was one of the few who spoke out against the House UnAmerican Activities Committee (HUAC) and helped get some organizations such as The Nation magazine out of HUAC’s clutches.

Shoes of an Extraordinary Man

After my months of research and readings, I feel enriched by what I have learned about Archibald MacLeish. I may not like his poetry or verse plays but I can say without hesitation that he is a man who deserves great respect for his accomplishments, his integrity in dealing with other people, and his acknowledgment of his own weaknesses. Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, and Ernest Hemingway could have never walked in his shoes.

Suggested Reading

By Archibald MacLeish:

The Irresponsibles: A Declaration (NY: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1940) [MacLeish’s call to social action and responsibility.]

J.B. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1958)

New & Collected Poems, 1917-1976 [includes “The Hamlet of MacLeish,” “Einstein,” “Conquistador,” etc.]

Poetry and Experience (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1960) [MacLeish’s treatise on how to write poetry.]

By other authors:

http://www.english.uiuc.edu/maps/poets/m_r/macleish/macleish.htm [read the section on MacLeish’s poem “Ars Poetica” and the bio notes which provide some insight about why his work has not survived well.]

Archibald MacLeish: An American Life by Scott Donaldson (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1992) [An insightful biography.]

Uphill with Archie by William H. MacLeish (Simon & Schuster, 2001) [A memoir by MacLeish’s youngest son.]

Archibald MacLeish: A Selectively Annotated Bibliography by Helen E. Ellis and Bernard A Drabeck with Margaret E.C. Howland (MD: The Scharecrow Press, Inc., 1995)

Thanks to Arthur Meiselman, editor/publisher scene4.com for allowing me to quote him. Thanks also to Grace Cavalieri and William Heyen. And my gratitude also to Ron Hussey and Houghton Mifflin for permission to reprint “You, Andrew Marvell.”

This essay originally appeared in the Memorial Issue, Volume 4:4, Fall 2003.

Karren LaLonde Alenier is author of seven collections of poetry, including Looking for Divine Transportation (The Bunny and the Crocodile Press, 1999), winner of the 2002 Towson University Prize for Literature, and The Anima of Paul Bowles (MadHat Press, 2016), selected as a 2016 top staff pick by the Grolier Book Shop in Boston. Her poetry and fiction have been published in the Mississippi Review, Jewish Currents, and Poet Lore. Her opera Gertrude Stein Invents a Jump Early On, with composer William Banfield, premiered by Encompass New Opera Theatre under the direction of Nancy Rhodes in New York City June 2005. For Scene4 Magazine, she writes a monthly column about Gertrude Stein and the arts called “The Steiny Road to Operadom.” To read more by this author: Five poems, Volume 3:4, Fall 2002; Audio Issue, Volume 9:4, Fall 2008