Volume 15:4, Fall 2014

A Splendid Wake Issue

Beginning in 1981 or 1982, Elisavietta Ritchie‘s home on Macomb Street NW in DC was the site of writing workshops. The house, a brick colonial shaded by mature trees, was a welcoming site, not far from the Cleveland Park Metro station. A group of poets met on Tuesdays to critique one another’s work in progress. Participants included: Elinor Castendyk Briefs, Maxine S. Combs, Lucia Dunham, Elizabeth Follin-Jones, Barbara Goldberg, Elaine Magarrell, Mariquita Mullan, Elizabeth Sullam, and Margaret Weaver. Another group of writers met monthly for a pot-luck dinners on Monday nights to socialize and share new work. Participants of this group included: Hilary Tham, Maxine Combs, Faith Jackson, Judith McCombs, Jonathon Agronsky, Jim Murrin, Phil Kurata, Karen Green, and occasionally Laura Brylawski-Miller, Terrance Mulligan, and Elisabeth Stevens. A smaller peer group workshopped fiction, meeting on Thursday nights, which consisted of Maxine Combs, Mary Edsall, and Elizabeth Follin-Jones. Elisavietta Ritchie served as host for all these events and, as she puts it, “nominal leader.”

This essay by Elisavietta Ritchie looks at three women who were stalwarts in the Macomb Street Workshops.

Maxine S. Combs

A lovely greeting card of a Japanese screen with a hillside of purple iris of staggered heights against the gold just slipped out of Maxine Combs‘s Handbook of the Strange, with her hand-written note to me, dated July 24, 2001, and her brand new nine-line poem, “Delicate Creatures.” It was Maxine who was delicate. She was fighting yet another variation of the cancer that had invaded her slender body some five years before, and was about to return to Johns Hopkins Hospital for radiation of “some spot on my liver—Hope nothing worse—I’ve been scribbling a little, paragraph here, a paragraph there, paragraphs not necessarily connected. My thought is that in time connections will be discovered. Or forged—Love, Max.”

A lovely greeting card of a Japanese screen with a hillside of purple iris of staggered heights against the gold just slipped out of Maxine Combs‘s Handbook of the Strange, with her hand-written note to me, dated July 24, 2001, and her brand new nine-line poem, “Delicate Creatures.” It was Maxine who was delicate. She was fighting yet another variation of the cancer that had invaded her slender body some five years before, and was about to return to Johns Hopkins Hospital for radiation of “some spot on my liver—Hope nothing worse—I’ve been scribbling a little, paragraph here, a paragraph there, paragraphs not necessarily connected. My thought is that in time connections will be discovered. Or forged—Love, Max.”

All the connections! Between paragraphs and people—the love.

Maxine Combs joined my poetry workshop, which began at the Writer’s Center then moved to Macomb Street, as my student, but it was soon obvious that she knew much more about poetry and American poets than I. She was, in fact, teaching literature at various universities in the District, Georgetown, Howard, eventually the University of the District of Columbia, and had published articles on such figures as Charles Olson. She never lorded her erudition over us, but shared her curiosity about many subjects, whether whimsical ideas or quotidian banalities or occult matters.

She had not, however, dared to publish her poems, and the little I was able to do for her was to encourage her to try. Journals began to accept her poems, as they did of other workshop members, while our workshops were evolving into a Tuesday poetry group and a Thursday fiction peer group which met around our expandable dinner table. Workshop participants bonded, and friendships evolved and would continue for years whether I was in town or not.

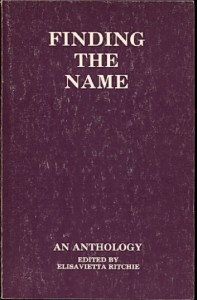

We created The Wineberry Press to produce our ten-poet anthology, Finding the Name, in 1983. When one compilation of Maxine’s poems was accepted as a broadside or brochure which turned out to be a shoddy print job, we put together a thin chapbook which our nascent Wineberry Press also published as Swimming Out of the Collective Unconscious: Poetry and Other Stories. And forward she went, to see journals and bigger presses publish individual pieces and more complete, full-length manuscripts of her poetry and fiction. She won the Larry Neal Award for Fiction and the Slough Fiction Award.

We created The Wineberry Press to produce our ten-poet anthology, Finding the Name, in 1983. When one compilation of Maxine’s poems was accepted as a broadside or brochure which turned out to be a shoddy print job, we put together a thin chapbook which our nascent Wineberry Press also published as Swimming Out of the Collective Unconscious: Poetry and Other Stories. And forward she went, to see journals and bigger presses publish individual pieces and more complete, full-length manuscripts of her poetry and fiction. She won the Larry Neal Award for Fiction and the Slough Fiction Award.

Our lives and interests and publishing adventures overlapped. Thus Dougald MacMillan, publisher of Signal Books which put out three of my books, was enthralled by Maxine’s writing and in 1995 published her Handbook of the Strange. Billeting Dougald in the “Baby Room” of our house, we held the launch at Macomb Street. In 1999 Calyx published The Inner Life of Objects. Meanwhile she became poetry editor of Antietam Review, which our fellow poet and writer Ann Brewer Knox edited. We went to Laurel Racetrack to bet on her husband Martin Bernstein’s horses, all three named after Maxine’s books.

And of course we all critiqued each other’s manuscripts, not daring to send even a love letter before it was vetted.

Our gang of fellow poets and writers shared not only the joys of writing, teaching and loving, but concerns about health, packrat partners, and troubled children who needed special schooling. We held auxiliary weekend workshops in our crumbing farmhouse by the Patuxent River, and above all, triumphal book launches and celebrations. With Elizabeth Follin-Jones and Mary Edsall, Maxine and her husband Martin threw a wedding reception for me and my husband Clyde in garden of their house. When we headed to Canada for over five years, returning for a few days only every few months, the workshops resumed, often at Maxine’s.

And when at various stages of her cancer, Maxine was largely confined to her house, we all visited. Toward the end, Ann Knox and I compiled and Wineberry Press published a little chapbook, Listening for Wings, following Maxine’s instructions for a cover photo of a swamp, and a particular shade of red to frame it. Whereas Maxine and Martin had been part of an ultra-reform minion which eschewed many rituals, Hilary Tham brought them into her conservative synagogue, what became Congregation Etz Hayim in Arlington, which albeit having a female rabbi, preserved many other traditions. And it was here that in 2002, Maxine’s final service was held, with several of us reading her poems, before moving on to a hillside in King David Cemetery in Falls Church, VA.

The final poem in Listening for Wings is “I Reach for Darkness.”

I Reach for Darkness

I reach for the darkness

and wonder:

Is it soft like roses

or the mists which roll in in the mornings?

Is it sweet like black plums?

Warm like a little campfire?

Does it conceal a treasure

like the mysterious oyster?

Or is it hungry like the great owl

perched in the black locust tree

steadily scanning for prey

eyes focused like headlights

on a road I can’t see.

Elizabeth Follin-Jones

When Elizabeth Follin-Jones joined the Macomb Street workshops, she had already worked on matters she could not discuss at Alamo, NM, taught English at National Cathedral School in Washington DC, painted canvases and, with “site specific sculptures” enjoying a certain vogue, Betsy created large fanciful statues of kangaroos and zebras.

When Elizabeth Follin-Jones joined the Macomb Street workshops, she had already worked on matters she could not discuss at Alamo, NM, taught English at National Cathedral School in Washington DC, painted canvases and, with “site specific sculptures” enjoying a certain vogue, Betsy created large fanciful statues of kangaroos and zebras.

The Tuesday afternoon workshops, which began at the old Writer’s Center and moved to Macomb Street, were dedicated to poetry. We created The Wineberry Press to publish Finding the Name, an anthology of three poems by each of the ten authors. Betsy took on the job of treasurer of the press, and also artist, sketching little clusters of wineberries as our press logo, and other little drawings for the postcards bearing our poems and solving the holiday greeting card challenge for several years.

Wineberry Press soon published a brochure of Betsy’s poems with her cover drawing of a Japanese salon, titled Nobody Here is Listening.

We tried to give Betsy what little support we could when her husband suddenly collapsed on the floor. She won a prize for her chapbook One Flight from the Bottom, with poems reflecting her loss, and illustrated the cover. She won a 2002 public art commission for a painted Poetry Bench, from the Bethesda Urban Partnership. She was also volunteering to help with incoming submissions to Poet Lore, based at The Writer’s Center, so to avoid conflict-of-interest issues we refrained from submitting our poems there.

Her arthritis worsened, and eventually we moved the workshop around her dining table in Chevy Chase, pausing to loosen recalcitrant lids of her jars and bottles, carry out her trash, and even pull a few weeds in her garden. Meanwhile she continued to hand on the New Yorkers which she had devoured.

When finally Betsy moved to the Grand Manor nursing home beside Sibley Hospital, we found her mini-apartment full of her artwork, and our books. At her rather poorly attended funeral at Gawlers, I read a couple of her poems…This one was on her poem-card.

Cold Rain

On the day we go to the cape,

it will rain cold rain.

The edges of flowers will fray.

A button will drop from your coat

in the cab while I pause to answer the phone.

It’s only your broker.

This year I’ll color my hair deep red,

wear skirts that slit at the knee,

hold your arm in the fog

on the dunes. Walk without shadow.

Who should be told if we both get lost

on our way out to dinner?

When we come home past the houses

shut tight to the eaves,

our hedge will look seedy.

The cat next door will desert

his post under the porch to greet us.

Our mail will catch in the jam:

we’ve been selected to win a prize.

The dentist announces his move

to an inconvenient location.

It will be raining cold rain as it always

rains on vacation. It will next year.

So far there has always been a next year.

Hilary Tham

Hilary Tham was apparently a familiar name in literary circles in Singapore when we lived up the Malaysian coast in Sungai Karang in 1976-1977. In Singapore, a professor handed me her first book and insisted I look for her. But at the time Hilary, born Buddhist near Penang, Malaysia, converting to Catholicism in school where she learned her English, then to Judaism when she married Peace Corps volunteer Joe Goldberg, was either now in South Korea or Washington.

Hilary Tham was apparently a familiar name in literary circles in Singapore when we lived up the Malaysian coast in Sungai Karang in 1976-1977. In Singapore, a professor handed me her first book and insisted I look for her. But at the time Hilary, born Buddhist near Penang, Malaysia, converting to Catholicism in school where she learned her English, then to Judaism when she married Peace Corps volunteer Joe Goldberg, was either now in South Korea or Washington.

I located Hilary in Virginia, but in the 1970s, with three little girls, she had no time for poetry. When she finally had a baby sitter, she joined our Macomb Street workshops, and turned out beautiful poems….I took them to Donald Herdeck, as his Three Continents Press, specializing in Third World writers, kept its office in the Flatiron Building in downtown DC. Three Continents published Paper Boats in 1987. Hilary’s other books regularly followed from other presses. In 1997, Three Continents published her Lane with No Name: Memoirs and Poetry by a Malaysian-Chinese Girl.

Hilary was also a fine artist, painting in Chinese style, and filling her little sketchbooks wherever she traveled. She created the cover of my skinny-but-prize-winning chapbook The Problem with Eden, and her later line drawings of our dacha by the Patuxent River still hang on the wall at Macomb Street. Isn’t this another way those we love remain with us?

Around 1990, Eli Flam invited me to become the poetry editor of his Potomac Review. Not only did I feel insufficiently knowledgeable for the job, but we were about to move to Canada for what turned out to be over five years. I looked around our Greater Washington poetry community for someone to recommend to Eli. A big consideration, along with selecting someone who was not overburdened with teaching, babies and other work, was how well that person would get along with others, meet deadlines and be fair in judging submissions. Hilary—who was forever learning more about poetry—rose to the top. Indeed, as Potomac Review poetry editor and frequent essayist for years, she showed herself knowledgeable, perspicacious, responsible, and fair.

Hilary was by now active with The Word Works press, and as Joe Goldberg was working for the World Bank, she took an active interest in their poetry programs. All this, while exploring Chinese traditions and superstitions, and creating her “Mrs. Wei” character who expressed novel opinions on many subjects.

She had by now become extremely knowledgeable about the Old Testament, and assumed the presidency of the Sisterhood at her synagogue. She put her faith into practice. While our close mutual friend Maxine Combs was battling the final stages of cancer, Hilary was often at their house on King Place, and became an immense help to Maxine’s husband Martin Bernstein, whom she brought into her synagogue. After Maxine died, Hilary sat shivah at their house.

The poem Hilary emailed to me the day she herself had just been diagnosed with an incurable form of cancer expressed gratitude for the joys life had given her, and emanated a mystical calm acceptance of impending death.

As if ever in Buddhist mode, Hilary wrote in her poem “Permafrost”:

The natives here are Aleut, Inuit, Yupit—word meaning

Real People, the rest of us are virtual,

visitors who come and go like summer wind, not real.

Washington Writers’ Publishing House held the annual competition for manuscripts, and the collection of Malaysian stories Hilary submitted had already won. Several of us, as well as Judith McCombs, line-edited the manuscript and proofed the galley. Hilary managed to paint the cover illustration, to approve the book, and finally see the finished book in print before passing away. WWPH published Tin Mines & Concubines in 2005.

We scattered dirt on her open grave, right beside Maxine Combs‘s grave at King David cemetery.

Superstition

The Chinese believe our dead return

as white butterflies on happy occasions,

to shed a blessing on the birth of sons,

to drink the moist scents of bridal teas.

White butterflies never appear at funerals

or at the pitch of familial battles

when Father smashed chairs and china

and Mother wielded words with equal violence.

Sister died young. I grew and left home.

The first time I returned, with my children,

Father was proud, Mother jubilant.

A white butterfly flew into the house.

“I Reach for the Darkness” by Maxine Combs reprinted from Listening for Wings (Wineberry Press, 1983). “Cold Rain” by Elizabeth Follin-Jones reprinted from Finding the Name (Wineberry Press, 1983), later reprinted in Nobody Here is Listening. “Superstition” by Hilary Tham is reprinted from Paper Boats (Three Continents Press, 1987).

Maxine Combs (June 1937—February 18, 2002) is the author of three novels, The Inner Life of Objects (2000), Handbook of the Strange (1996) and The Foam of Perilous Seas (1990), and two poetry books: Listening for Wings (2002), and Swimming out of the Collective Unconscious (1999). She moved to Washington, DC in the early 1970s and taught English at several universities, including American University (1970-1964), George Mason University (1979-1988), Howard University (1988-1989) and the University of the District of Columbia (various years from 1972 to 1990). Combs won the Larry Neal Award for Fiction (1998) and the Slough Fiction Award (1990), and grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the DC Commission on the Arts, and a fellowship from the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She was a fiction editor for The Antietam Review.

Elizabeth Follin-Jones (April 29, 1924 - June 6, 2011) grew up near Philadelphia and attended the University of Michigan, graduating with B.A. in mathematics. A longtime resident of Chevy Chase, MD, she was the author of the chapbook One Flight from the Bottom, winner of the 1990 Baltimore Artscape Literary Award for Poetry. Her poems are included in the anthologies Finding the Name, Cabin Fever: Poets at Joaquin Miller's Cabin 1984-2001, and Winners: A Retrospective of the Washington Prize. One of her short stories won a PEN Syndicated Fiction Project award. Individual poems of hers appeared in Poet Lore, Passager, and Embers.

Elisavietta Ritchie has translated poems mainly from Russian and French, but also Macedonian, Malay and Indonesian. Seventeen of her poetry collections have been published, including Guy Wires (Poets' Choice Publishing, 2015), Tiger Upstairs on Connecticut Avenue (Cherry Grove, 2013), Feathers, Or, Love on the Wing (Sheldon Studios, 2013), From the Artist's Deathbed (WinterHawk Press, 2012), Cormorant Beyond the Compost (Cherry Grove, 2011), and Real Toads (Black Buzzard Press, 2008). She served as President of Washington Writers' Publishing House from 1983 to 1986, and president of their fiction division from 2000 to 2010. Ritchie founded Wineberry Press. She edited the anthologies The Dolphin's Arc: Endangered Creatures of the Sea (SCOP Publications, 1989), and Finding the Name (Signal Books, 1983). A co-founder with Myra Sklarew of A Splendid Wake, an organization to honor deceased poets in the Greater Washington Area, she works currently as a writer, editor, mentor, workshop leader for creative writing, journalist, photographer, poet in the schools and translator.www.elisaviettaritchie.com To read more by this author, see poems from the Fall 2002 issue, and her essays on Betty Parry and John Pauker.

Hilary Tham (August 20, 1946 - June 24, 2005) is the author of nine books of poetry (including Counting, The Tao of Mrs. Wei, and Bad Names for Women), a collection of short fiction (Tin Mines and Concubines), and a memoir (Lane With No Name). She was born in Klang, Malaysia; after her marriage in 1971, she immigrated to the US, where she converted to Judaism, and raised three daughters. She was Editor-in-Chief for The Word Works, Poetry Editor for the Potomac Review, and taught extensively as a visiting writer in schools throughout Virginia. To read more by this author: Hilary Tham: Winter 2001 Hilary Tham: Whitman Issue Hilary Tham's Introduction to Activist Poets Issue, Fall 2002 Hilary Tham: DC Places Issue Hilary Tham: Audio Issue