“Romantic, realist, comedian, satirist, relentless and indefatigable brooder upon the most ancient mysteries—Nemerov is not to be classified.” – Joyce Carol Oates

“We write, at last, because life is hopeless and beautiful.” – Howard Nemerov

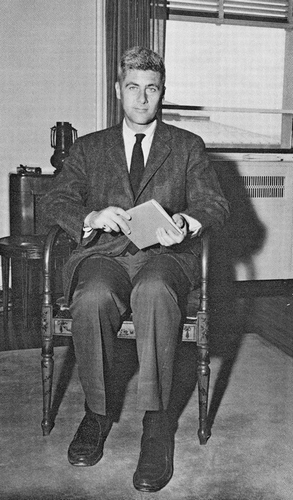

Howard Nemerov in the Poetry Office, Fall 1962. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Howard Nemerov (February 29, 1920 – July 5, 1991) was among the rare group of poets to serve more than once as Poet Laureate/Consultant in Poetry; he held the position in 1963-64 and again in 1988-90. Between those two terms he won many of the major poetry prizes. And during his second tenure he did something no poet had ever done: read a poem before a joint session of the U.S. Congress.

The occasion was a celebration of the bicentennial of the Congress. Nemerov was asked to write a poem by then-historian of the U.S. House of Representatives Ray Smock, who recounted the event a few years ago on the blog of the Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education at Shepherd University in West Virginia. According to Smock, the first poet to speak before Congress was Carl Sandburg, who in 1959 talked about Abraham Lincoln on the 150th anniversary of his birth, but Sandburg did not read poetry during his talk.

Smock wrote that he “never even thought of imposing any requirements” on Nemerov when he made the request; the laureate “could have lambasted the Congress.” Looking back, Smock compared Nemerov’s poem to one written by John Greenleaf Whittier, who wrote about the Congress that convened in December 1865, just after the end of the Civil War. Smock wrote:

They both took the poet’s role of admonition and warning and of urging Congress to rise to noble purposes because so much was at stake.

Both poets assumed Congress was important to the life of the Republic. Both poems recognize the frailty of politicians and the difficulty of harnessing human passions. From time to time the members of Congress, and the people who elect them, need to be reminded of these things by poets and other artists who do not have the same axes to grind as journalists, political activists, or television commentators.

On the floor of the House of Representatives on March 2, 1989, Nemerov was introduced by Minority Leader Robert Michel, the highest-ranking Republican in the House. His introduction and Nemerov’s reading are recorded in the Congressional Record. Here’s Michel:

If I may paraphrase one of our former congressional colleagues, the Members of the First Congress left us a legacy far above our power to add or detract by our record, and at this point in our celebration, therefore, what we need is not more congressional prose, but the fiery, living truth of great poetry.

We are very fortunate indeed to have with us today the Poet Laureate Howard Nemerov. His work has been described as modern sensibility with classic elegance. He has been the recipient of the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, the National Medal of Arts and, among other recognitions, the prestigious Bollingen Prize for poetry in 1981. He is also a novelist, essayist, critic and teacher, a consultant to the Library of Congress, and a distinguished professor of English at Washington University in St. Louis.

Now, if these achievements were his only contribution to our civilization, he could be content, but he made another kind of commitment. During World War II he flew more than 100 combat missions with the Royal Air Force and later with the U.S. Air Force.

Howard Nemerov was once asked about the problem of poetic inspiration, and he said, `The impulse comes from unexpected oddities.’ Unexpected oddities sounds much like what goes on in some of our debates, so he should feel right at home here on this floor of the House.

Mr. Speaker, ladies and gentlemen, it is my pleasure to introduce the Poet Laureate of the United States, Howard Nemerov.

Poet Laureate Howard Nemerov reads “To the Congress of the United States Entering Its Third Century, With Preface” to a joint session of Congress. Courtesy of the collection of the U.S. House of Representatives.

Nemerov responded by saying, “Well, this is going to be an anticlimax; isn’t it, after an introduction like that?” Then he read his poem, which reflects the humor that often infuses his work while commenting on the history of Congress and the checks and balances built into the federal system by the nation’s founders:

To the Congress of the United States Entering its Third Century, With Preface

Because reverence has never been America’s thing, this verse in your honor will not begin `O thou.’ But the great respect our country has to give may you all continue to deserve, and have.

Here at the fulcrum of us all,

The feather of truth against the soul

Is weighed, and had better be found to balance

Lest our enterprise collapse in silence.For here the million varying wills

Get melted down, get hammered out

Until the movie’s reduced to stills

That tell us what the law’s about.Conflict’s endemic in the mind:

Your job’s to hear it in the wind

And compass it in opposites,

And bring the antagonists by your wits.To being one, and that the law

Thenceforth, until you change your minds

Against and with the shifting winds

That this and that way blow the straw.So it’s a republic, as Franklin said,

If you can keep it; and we did

Thus far, and hope to keep our quarrel

Funny and just, though with this moral:Praise without end for the go-ahead zeal

Of whoever it was invented the wheel;

But never a word for the poor soul’s sake

That thought ahead, and invented the brake.

Nemerov as Writer

As Michel noted in his introduction, Nemerov was a prolific and much-honored writer. A remembrance published in “The Gazette,” the Library of Congress’s internal newsletter after his death from cancer in 1991 reported that he authored 26 volumes of poetry, criticism, fiction, and short stories. He taught at Hamilton College, Bennington College, and Brandeis, before beginning his long affiliation with Washington University of St. Louis in 1969. He was a chancellor of the American Academy of Poets, a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and a member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters.

Nemerov’s first book of poetry, The Image and the Law, was published in 1947; he dedicated it to John Pauker, with whom, along with Reed Whittemore, Nemerov worked on Furioso magazine. The poem “The End of the Opera” was published in The New Yorker in 1991 just before Nemerov died.

A review by Irving Howe of Poetry and Fiction: Essays by Howard Nemerov, published by Rutgers University Press during his 1963-64 term as consultant, described Nemerov as “a man of letters” in “the best, the old-fashioned sense of the term.” Wrote Howe, “He commands a notable portion of learning, and is free of the national prejudice that using one’s mind somehow drains one’s ‘creativity.’ And he enjoys writing about books, not in behalf of any critical doctrine, but with a humane feeling for the possibilities of literature.” Another review praised the curiosity reflected in the book, and said “each essay, felicitously written and never far from wit and a well-turned pungent phrase, makes highly entertaining reading.”

The Collected Poems of Howard Nemerov, which included poems published between 1945 and 1975, won the Pulitzer and a National Book Award. In 1978 he won the Theodore Roethke Memorial Prize for Poetry, and in 1987 he was chosen the first winner of the Aiken Taylor Award for Modern American Poetry, administered by the Sewanee Review and the University of the South. That same year he was awarded a National Medal of Arts. When asked by Grace Cavalieri in a 1988 interview if there were any poetry prizes he hadn’t won, Nemerov quipped, “A lot. I’m sitting waiting with my hands out. I don’t know what’s taking them so long except for the unfortunate circumstances that there are other poets.”

Cavalieri’s interview, which took place on the day of Nemerov’s inauguration as Poet Laureate, got him talking about his writing. Asked whether he liked the poems in a manuscript he was currently working on, he said, “I like all my children, even the squat and ugly ones.”

“I sometimes talk about the making of a poem within the poem,” he told Cavalieri. He said his poem “Poetics” was “as close as I come to telling how I do it.” He told her that he wrote in bursts, maybe 20 or 30 poems in a couple of months, followed by “long sterile periods.”

When asked about the humor in his poetry, Nemerov had this to say:

When I was starting to write the great influence was T.S. Eliot and after that William Butler Yeats. I got, of course, the idea that what you were supposed to do was be plenty morbid and predict the end of civilization many times but civilization has ended so many times during my brief term on earth that I got a little bored with the theme and in old age I concluded that the model was really Mother Goose, and so you can see this in my new poems.

Cavalieri commented, “I would say that in some of your early poems you would argue your way into Heaven. You were so tough with God.” Nemerov responded, “I still am. Somebody asked me ‘Do you believe in God now?’ I said, ‘No, but I talk to him much more than I used to.’”

Cavalieri asked Nemerov about his plays Cain and Endor. “Jim Dickey told me once that he found the last part of the Cain play more moving than anything in Shakespeare,” Nemerov told her. “That was a nice thing for him to say, though I don’t believe it.”

In announcing Nemerov’s second appointment in 1988, succeeding Richard Wilbur, Librarian of Congress James Billington wrote, “Howard Nemerov has given America a remarkable range of poetry, from the profound to the poignant to the comic. He is also an outstanding critic, essayist, fiction writer, and teacher.”

Nemerov’s obituary in the Washington Post touched on both his range and evolution as a writer:

Critics of his poetry noted not only its more technical side, such as his mastery of rhythm, diction and imagery, but also his sardonic satire and wit, the broad range of subject matter and his underlying pessimism about the human condition. …

In general, his work encompassed early poems highly influenced by the masters of poetry, a middle period of bitter ironies and almost exhaustion, and his last, seemingly more mellow work.

That obit said that Nemerov was “not a fan of overtly political poetry.” But he did deal with political topics, as he did in “To the Governor & Legislature of Massachusetts,” in which he described his dismay upon learning that to take a teaching job in the state he was required to sign an oath of loyalty to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Cognizant of his new mortgage, he signed, but he also imagined a day when he might “shove the Berkshire Hills / Over the border and annex them to Vermont, / Or snap Cape Cod off at the elbow and scatter / Hyannis to Provincetown beyond the twelve-mile limit…”

When Robert Pinsky became Poet Laureate in 1997, he launched the “Favorite Poem Project,” which encouraged people to share their favorite poems. Then-first Lady Hillary Clinton read Nemerov’s “The Makers,” which celebrates the first unknown-to-us poets, whom the poem describes this way:

They were the ones that in whatever tongue

Worded the world, that were the first to say

Star, water, stone, that said the visible

And made it bring invisibles to view

Clinton said she chose the poem to read at a millennium evening at the White House “to celebrate the timeless power of America’s poetry and poets.”

Nemerov and the Library of Congress

Nancy Galbraith, head of the library’s Poetry Office at the time of Nemerov’s death, “admired his clear vision, enjoyed his intelligence, and relished his lack of pretension and his accessibility as a person as well as a poet.” The admiration was mutual. Nemerov felt genuine affection for the Library of Congress, with which he had a nearly thirty-year relationship.

Howard Nemerov and Reed Whittemore. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

He first read at the library in April 1962, and he returned later that year for the National Poetry Festival. (It was at that festival that poet-critic Randall Jarrell, a former laureate, opined on the strengths and weaknesses of more than two dozen American poets; Nemerov was only mentioned among those “interesting and intelligent” poets that Jarrell would like to have written about “if I had room.”)

At the festival, Nemerov gave an address he titled “The Muse’s Interest,” in which he said to his fellow poets:

So if we incline to complain over the want of a large public it might reasonably if rudely be said to us, as it used to be said in the air force, Nobody drafted you, you volunteered.

All this does not in the least mean that poetry relinquishes its large claim on the world, its claim to teach the world, its prophetic claim on the ultimate realization of all possibility. For the whole business of poetry is vision, and the substance of this vision is the articulating possibilities still unknown, the concentrating what is diffuse, the bringing forth what is in darkness.

The following year, Nemerov began his first term as Consultant in Poetry. It was a busy year, as documented in the Poetry Office archives at the Library of Congress. (Files from Nemerov’s second term are not yet included in the publicly available poetry office archives at the Library.)

Nemerov’s first lecture as Consultant in Poetry was called “Bottom’s Dream: The Likeness of Poems and Jokes.” In it he talked about the poetic possibilities inherent in everything from newspaper typos to modern-era absurdities like the story of a fighter jet so fast it was shot down by its own gunfire.

In the fall of 1963 he took part in a discussion of Latin American poetry sponsored by the Latin American Forum of Georgetown University and the embassy of Chile. Among the poets discussed by the panel, moderated by Chilean writer Fernando Alegria, were Gabriela Mistral, Pablo Neruda and Nicanor Parra.

In an internal report evaluating the library’s recordings of poets, Nemerov had both praise and criticism for the collection. He also reported an epiphany: listening to one recording had led him to completely reevaluate his opinion of a poet:

Hearing George Barker was an even more dramatic experience, involving a complete reversal of a previously held opinion. For I knew George, in New York, back at the beginning of the War, but haven’t seen him since. Nor had I kept up with his work, having by about 1947 arrived at the view that he was a shriller more hysterical and less responsible version of Dylan Thomas. His reading convinced me I was absolutely in error, and I have been reading through his poetry, all of it, since then, with a growing sense of discovery (to give credit where due, I should add that George Barker’s appearance in Oscar Williams’s new anthology, a copy of which had come the day before, was instrumental in my electing to hear George Barker’s tape.)

Nemerov wrote to Barker in London to tell him “how great a pleasure it’s been getting acquainted all over again with your tough and funny grandeurs” and saying his poems “seem to have gained an immense character of decisiveness in the years since we met.”

Nemerov also wrote a fan letter to British writer Owen Barfield, who he did not know, gushing over Barfield’s book Poetic Diction. Nemerov told Barfield that he had read the book maybe half a dozen times, and offered to help him find an American publisher. In a letter pitching the book to McGraw-Hill, Nemerov wrote, “I have enjoyed it, admired it, and, hopefully, learned from it, for maybe fifteen years, during which I almost never ran across an American poet or teacher who knew of it independently of my telling him of it; certainly it is time the rest of the literary community got to know about this book—which, I might add, they look to be in fairly desperate need of.” (You can now buy a paperback copy, with a foreword by Nemerov, from Wesleyan University Press.)

Nemerov used his position to advocate for poets to be paid for appearances. In a 1963 response to a request from the National Society of Arts and Letters, he said he assumed no honorarium was being offered because none had been mentioned. He told the group that his minimum fee was $200 and offered to return half to the group’s scholarship fund. Part of his response:

The poet is so placed in our country that he can earn only negligible sums by the direct practice of his art; nothing like a living wage is even contemplated. But the by-products of his art, the lecturing, the teaching, writing, which devolved from the fact of his doing poems, can enable him to live, and on the monies brought by these activities he is compelled to rely.

I regret that this is so, and have made exceptions, where poverty, enthusiasm, and prior personal acquaintance have been involved. But this rule is that public performances are done for money, even if it is generally not very much money. This is partly for the economic reasons just outlined, and partly minimum because such performances cost me, in addition to time, the labor of preparation and considerable anxious apprehension.

Nemerov made a similar point in a letter to Pat Udall, wife of the Arizona congressman:

Thank you for inviting me; the thought is a kind one, and I hope my gracelessly evading the invitation won’t be an obstacle to our acquaintance, which began so well. But I think the rule that this sort of thing may be done only for money is breakable only in favor of the young and poor—school children, for example. For there appears to be, not only here in Washington but yet rather strikingly ubiquitous here in Washington, an implicit assumption on the part of clubs and societies, &c., that the poet is in business to improve his reputation, make himself popular, sell a few books, and mingle with the mighty. But I ain’t in that business. I make the stuff, such as it is, and cannot live on what I get paid for doing that, so you can see that if I moonlight in distributing culture now and then it has to be purely for the cash.

Nemerov did enjoy engaging with young people. Toward the end of his first term, he responded to a letter of thanks from Charlotte Brooks, the head of the English Department of the DC Public Schools:

Many thanks for that very kind letter. The last seminar went off pleasantly; I thought it as good as the first one (in the middle two I am afraid I got a it nervous and tried to do it the safe way, as if I were teaching a class, so those were rather more routine; we learn and learn, but maybe not fast enough).

I’ve enjoyed giving these seminars, and wish I’d thought of the idea earlier so that there might have been more of them. The students, once they got past their shyness, were a constant delight. And of course it is most gratifying to hear that you intend to continue and develop what we were able to begin.

The Library of Congress archives make it clear that Nemerov (like Randall Jarrell and presumably many others to hold the position) received many unsolicited poems and manuscripts from writers or their loved ones, seeking his opinion and advice. It’s remarkable how thoughtfully he responded to some of them, with letters suggesting he had indeed spent time with the poems. He was kind but could also be quite frank.

In one three-page letter that engaged deeply with a poet’s work, Nemerov suggested that the writer was a bit too strongly influenced by Robert Lowell; Nemerov offered that he himself was about 32 before he began to sound more like himself than the people whose writing influenced him. And he added:

You have obviously a very strong talent, as well as being intelligent about the art and somewhat learned in its ways. If I’ve stressed the things that might remain do be done, rather than what you have already done well, I take it that’s the job you wanted me to do, or else you wouldn’t have sent me the poems.

To a woman who sent her poems, saying “they are a part of me” and asking for his opinion at his earliest convenience, he wrote:

It is very kind of you to value my opinion on things having to do with poetry, and to have sent your poems.

It is quite clear, though, that you are an amateur at writing, as you acknowledge; and I will allow, in turn, that the writing of poetry can give the writer a meaningful experience and a deep pleasure, even if the results of that writing cannot meet the standards applied by professional poets—standards which should not, indeed, be applied to such work as you have sent, work that really achieves its purpose in the writer’s own feeling of satisfaction at having expressed his own feelings.

In response to a poem sent by someone at the White House to the Veterans Administration, which forwarded it to Nemerov with a request for “an informal appraisal,” Nemerov wrote: “If this poem would actually and in fact put an end to war and inaugurate eternal peace, I still don’t think I would print it. I hope this appraisal is informal enough.”

His wit was not reserved for creative writing. When Nemerov received a short blunt note from the credit manager at Brentano’s bookstore rejecting his request for a charge account, Nemerov’s response was memorably snarky:

Dear Mr. Saul,

The habit of writing curt notes will doubtless have accustomed you to receiving the same from others; and you will naturally understand that the contempt I feel is not for you personally, since there is no reason in the world for you to have known my name. …

The attached biography may perhaps explain my claim to be considered as a customer at your store. No reply is necessary, however, as the slight inconvenience of not entering Brentano’s is one I am extremely willing to put up with.

His sharp wit can also be seen in a 1964 letter to the editor of the Washington Post:

Your Staff Reporter Willard Clopton, reviewing a record of poetry readings issued by the Library of Congress, spends half his space listing his disqualifications for the task, which are indeed imposing. He is wrong, however, in regarding himself as exceptional in this respect; poetry is practically always reviewed by people who dislike it and are ignorant of its nature; Mr. Clopton is only more candid than they.

Nemerov was asked to stay for a second year during his first stint, and while he turned it down, he wrote to Librarian of Congress Quincy Mumford that he felt “very much at home” at the library even though “the position itself has been sometimes puzzling for me, and there are many things I might have learned to handle better than I have done.”

Between his terms, Nemerov participated in Consultants’ reunions which were held at the Library of Congress in 1978 and 1987. After the 1978 reunion, Nemerov wrote that walking into the library again “brought back the feelings almost of awe, and now accompanied by nostalgia, that always attended even my daily entrance into the place when a consultant.” In a 1987 letter to Nemerov by Assistant Librarian for Research Services John Broderick, the librarian thanked Nemerov for stopping by to visit him after the 1987 reunion.

You were my “first” Consultant, and barely a month after arriving here in 1964, I had the task of working with you on revising the Library’s brochure for soliciting literary papers. Your stance then as now was cynical but understanding—on you, a good combination.

During Nemerov’s second term as laureate, he wrote “Witnessing the Launch of the Shuttle Atlantis.” He had previously written “On an Occasion of National Mourning,” about the 1986 explosion of the space shuttle Challenger.

His Challenger poem has some similarities with “Upon the Murder of the President,” a poem he wrote during his first term as consultant, in response to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. Both remark on how quickly people can turn from grief back to daily life.

After the Kennedy assassination, Nemerov turned down a request from Basic Books to contribute his poem to an anthology about the late president. “I did indeed write a poem on that occasion,” he wrote, “and even let a piece of it be printed, but the result strikes me now as having been rather willed, although sincerely so, than fully imagined, and I am not willing to see the piece reappear in your anthology.” The poem—at least the draft included in the Library’s archives—is striking in its depiction of the history of racist violence in the U.S. and “our will to hatred and the arrogance of wealth.” It includes this stanza:

Now, citizen, consider. It will do no good

To say the man who pulled the trigger was insane

Or Communist-inspired. That excuse may serve by day,

But what of the night, the evil hatred born of fear

That eats the heart? Did that man, by his distant kill,

Reflect the people of our country to themselves?

And it ends with this one:

Sorrow is easy, America, we are a people

Quick to the handkerchief. Maybe our tears can be

Impounded behind a dam and used to turn the wheels

Of some concern whose wastes will more pollute the waters.

Maybe our tears will poison all the Russians. Maybe.

Sorrow, America, and while you sorrow, think.

Works Cited

Robert C. Byrd Center for Congressional History and Education, The Byrd Center Blog, “Two Poets on Congress,” April 14, 2015: https://www.byrdcenter.org/byrd-center-blog/two-poets-on-congress

Library of Congress, The Gazette, Vol. 2, No. 29, July 19, 1991, “Galbraith Remembers: Howard Nemerov and His Young Listeners,” by Gail Fineberg: http://loc.gov/rr/program/bib/nemerov/nemerov2.pdf

“The Poet and the Poem,” Grace Cavalieri, “A Conversation with Howard Nemerov,” recorded at the Library of Congress October 1988 (transcription): https://www.gracecavalieri.com/poetLaureates/howardNemerov.html

Washington Post, “Howard Nemerov, Pulitzer Winning Poet, Dies at 71,” by Richard Pearson, July 7, 1991: https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1991/07/07/howard-nemerov-pulitzer-winning-poet-dies-at-71/932aa8bb-d5b4-4084-ba39-f2e4e3bc6ec1/?utm_term=.efb29253d2cf

Favorite Poem Project, “The Makers” by Howard Nemerov, read by Hillary Rodham Clinton, First Lady of the United States, March 28, 2016: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xeGTOYpyaLU

Washington University Digital Gateway, Modern Literature Collection, Program for “Howard Nemerov Reading Selections from His Poems” at the Library of Congress, April 16, 1962: http://omeka.wustl.edu/omeka/exhibits/show/mlc50/item/8804

Peter Montgomery, “Randall Jarrell in Washington,” Beltway Poetry Quarterly, Vol. 10:4, Fall 2009: https://www.beltwaypoetry.com/randall-jarrell/

Peter Montgomery is a DC-based freelancer who writes primarily for progressive nonprofits and media outlets. He is a senior fellow at People For the American Way and contributes to its Right Wing Watch blog. To read more by this author: Peter Montgomery: Mapping the City