Self-Portrait as Venus

After Sandro Botticelli

Oh, so this is the world?

Wind gods blowing over-

due vowels with rounding mouths.

Sky above, sea beneath, and I

am between. This is the world

divided: two people

with different wants.

One places delicate detail

of petals, narrates stories

always already in star. The other

moves the tide that rises, promises

to swallow me whole.

Gentle Obsessions

After Emily Dickinson

When I folded the memory

of your death into an accordion shape

and tossed it to sea, I was certain it would play

a hymn like the ones you loved. And you were right:

the soul knows how to sustain itself

despite submersion, to give up the land’s edge

lost to the flood until everything is the horizon.

When you said spring leaves only water

whole, did you mean the sky and ocean are

windows? When nothing can be tethered

to shore by phone line or otherwise,

which practices survive?

Wistful Theory

Johnson, Vermont

No hopeless field nearby, no whisper

moving through the body’s hull.

Today, silence. Even emptiness

yearns for something.

Today, a steep walk, my face lashed

by wind and snow. The bivouac of birds undone,

replaced by milkweed’s collapsed casket.

The moment before this landscape’s erasure

will be a prophetic sigh. No, it

will be the stillness of water’s fine lie.

Via Negativa

Let white light erase

the landscape until all

becomes snow or scrimshaw.

The present always wants

another passing between

worlds: more

than living and—

My body composes

its own sentence.

Tentatively starts

and stops. Stop

down: to allow less

light. Which is to say

gravity. There are ways

to contain a thing

without binding it

in twine.

How to Prove a Theory

For John

And on our second date you told the story

of your family in China, which you began

in jest, I have to have a son. You moved

food around your plate. Shared how your father,

the second born, felt birth order made his choices

less consequential until his older brother,

the opera star, died of appendicitis. How familial

attention shifted to him as if the singer

had never lived to intone a note. After, your father

became a Catholic priest in part because the vows

disallowed the children expected of him

as the only living son. Later, Communists came,

held your grandfather captive, demanded ransom

before taking the family home. The priest boarded

the last flight out of Beijing to San Francisco,

asylum granted, before settling in D.C. where he met

your mother, renounced his vows, fell in love,

and fathered two sons. But you have a brother!

I shouted as if problem-solving because then

you did. I loved you before the doctor’s warning,

Things with your brother are dire. Before Paul’s

final night when you spoke slowly as morphine’s drip.

To prove a theory of the beauty of this world,

acknowledge its cruelty: the brother lacking children

is less likely to be given a new heart so he’s fated

to spend two years choking as if drowning but remains

thankful for each night he falls asleep with his head

in your lap, for the bandages we wrap at the ankles

once edema takes hold. That night, you told me

your grandfather died before he got word your father

was a father, despite such an unlikelihood.

Then, when you were eleven you watched as his heart

stopped in front of you. You were sent to school

later that afternoon. It was April Fool’s Day. When

you told people your dad was dead, few believed you.

To prove a theory of fragility, you will master capacity:

to fill hallowed air with laughter, even after the hardest day

with the help of a book titled Terribly Offensive Jokes

Volume 1, discovering seven more in the set, recalling

Paul tell each line as if his own. And before you lead

our way home, you will pretend to drop the ashes

that had been his body as Paul would have done

to you. For a second, your lineage suspended,

its weight contained. And yet these generations are

mirrors for looking into. Only you remain. And yet.

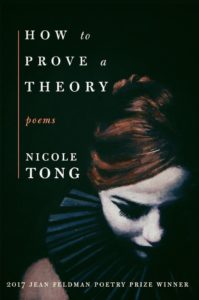

All poems reprinted from How to Prove a Theory (Washington Writers Publishing House, 2017), with permission from the author. An earlier version of “Gentle Obsessions” appeared in Rust + Moth, Autumn 2014 issue.

Washington Writers Publishing House is a non-profit organization that has published over 50 volumes of poetry since 1973 and nearly a dozen volumes of fiction. The press sponsors an annual competition for writers living in the Washington-Baltimore area. WWPH is a cooperative, and winners of the annual competition become members of the collective, working on publicity, distribution, production and fundraising to continue the vitality and success of the press.

Nicole Tong is the author of How to Prove a Theory (Washington Writers Publishing House, 2017), winner of the Jean Feldman Poetry Prize. She is the recipient of fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and George Mason University, where she received her MFA. In 2016, she served an the inaugural writer-in-residence at Pope-Leighey House, a Frank Lloyd Wright property in Alexandria, VA. She is a recipient of the President's Sabbatical from Northern Virginia Community College, where she is a Professor of English. Her writing has appeared in American Book Review, Calyx, Cortland Review, and Yalobusha Review.