Joseph Brodsky was the fifth U.S. Poet Laureate (serving from 1991-1992 at the Library of Congress). This interview was originally conducted at the Library of Congress on October 1991, and was broadcast on “The Poet And The Poem,” on public radio station WPFW-FM. It was first published in the American Poetry Review in 1992. It has never been seen online.

A native of Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, Joseph Brodsky’s poetry has been published in twelve languages. He lived in the U.S. since 1972 when he was exiled from the Soviet Union. He was the recipient of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Award. His essay collection, Less Than One, was awarded the 1986 National Book Award for criticism. He won the 1987 Nobel Prize for Literature.

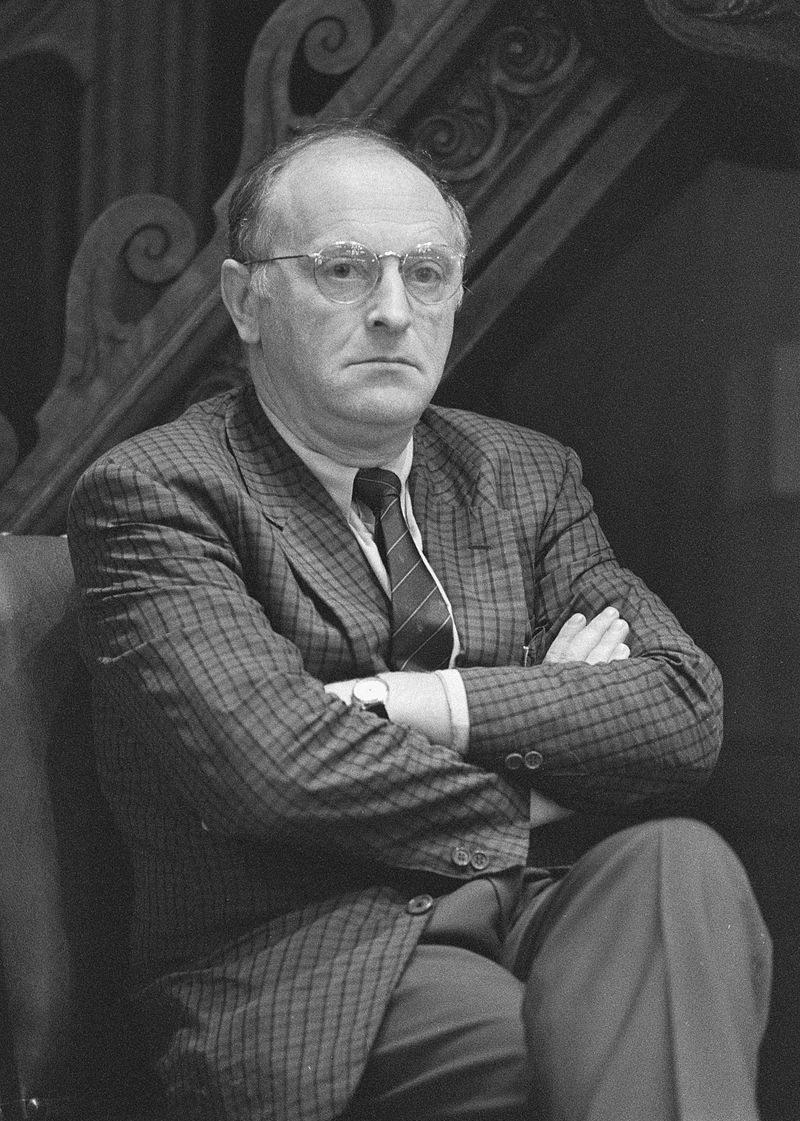

Photo: Dutch National Archives, The Hague

Grace Cavalieri: Your initial address at the Library of Congress (October, 1991) was also published in The New Republic. Here you present yourself as an activist for poetry, an enthusiast: “The poetry consultant as the poetry activist.” Is that how you wanted to be received?

Joseph Brodsky: It’s fine if people feel that way but the main point is simply I honestly regard that this job, being paid by the Library of Congress in Washington, makes me the property of the public for this year. It is in the spirit of the public servant. My concern is the public’s access to poetry which I find very limited, idiotically so, and I would like to change it if I can.

Cavalieri: Do you think you can?

Brodsky: It takes more than a speech preaching to the converts here at the Library. It takes publishers, entrepreneurs, to throw money into the idea.

Cavalieri: In addition to wanting more poetry published and distributed you bring a new view to American poetry. Would you tell us some of your feelings about this country’s poetry?

Brodsky: Basically, I think it’s remarkable poetry, a tremendous poetry this nation has and doesn’t touch. To my ear and my eye it’s a nonstop sermon of human autonomy, of individualism, self-reliance. It’s a poetry hard to escape. It has its own faults and vices but it doesn’t suffer malaise typical of the poetry of the continent—Europe—self aggrandizement on the part of the poem, where the poet regards himself as a public figure … all those Promethean affinities and “grandstanding.” Those things are alien to the generous spirit of American poetry, at least for the last century. The distinction of an American poet from his European counterpart, in the final analysis, is a poetry of responsibility … a responsibility for his fellow human beings. This is a narrowing of the ethical application of poetry. What a European does—French, German, Italian, Russian—is move his blamethirsty finger. It oscillates 360 degrees all the time, trying to indicate who is at fault, trying to explain his and society’s ills. An American, if his finger points at anything, it’s most likely himself or the existential order of things.

Cavalieri: And you call this a sermon of resilience?

Brodsky: Yes if you like.

Cavalieri: You were exiled from Russia in 1972, having previously been sentenced to five years hard labor at an Arctic labor camp. Did the efforts of Russian intellectuals and writers win your release?

Brodsky: Not only those. People abroad too. One person who interceded in my behalf was the father of the H-bomb, Edward Teller.

Cavalieri: And you then accepted the invitation to come to this country?

Brodsky: I was put on a plane going only in one direction with no return ticket and a friend of mine from the University of Michigan, now dead, Carl Proffer, a great man, a professor of Slavic languages, met me and asked how I would like to come to the University of Michigan as poet in residence.

Cavalieri: That young man, all those years ago…

Brodsky: Almost twenty.

Cavalieri: He was such a brave stubborn independent man. Do you feel that he’s still with you? Do you know that man now?

Brodsky: He is still within me. Those years in Michigan are the only childhood I ever had.

Cavalieri: In reading the transcripts of your trial I was struck with how unafraid you sounded. How did you feel?

Brodsky: I don’t really remember. I don’t think I was afraid. No. I knew who runs the show. I knew I was on the receiving end so it didn’t really matter; I knew what it would boil down to.

Cavalieri: I was wondering when watching the Clarence Thomas hearings recently how you might feel while watching them…the way they were doing business…having been on the hot seat once yourself, and watching something so vastly American and unwieldy as those hearings. In a way it could only happen in America.

Brodsky: I felt very upset with a bad taste in my mouth. It wasn’t really a court case. I felt it was utterly ridiculous and people often find themselves in the predicament choosing between two things where neither one is good.

Cavalieri: I would have liked to see a poet as questioner. We would have gotten a different approach.

Brodsky: I wouldn’t question Judge Thomas. I know enough about the transaction between the opposite sexes not to question him on that score.

Cavalieri: Do you write poetry primarily in English now?

Brodsky: Poetry I write primarily in Russian. Essays, and lectures, blurbs, reference letters, reviews, I write in English.

Cavalieri: How much are we missing? We see and hear English translations of your poems and some are called brilliant in any language.

Brodsky: You can’t say you are missing much. You can’t say you are missing the prosody of another language. You can’t miss the acoustics of another language. The original is rooted in the euphony of the Russian language. That of course you can’t have and you’re not missing it. You can’t miss something that you don’t know.

Cavalieri: We can get a good lyrical poem anyway that is matchless.

Brodsky: That’s what it is if it works in English. You have to be a judge of solely how it is in English.

Cavalieri: We shouldn’t feel we’re getting only ninety percent of something which is absolute.

Brodsky: You get a poem in English, good or bad. You can’t fantasize about what it’d be like in the original.

Cavalieri: I was watching you recite recently without looking at the page. Can you recite every one of your poems in Russian?

Brodsky: By heart? I don’t think so. Not any longer. Until I was forty I knew them all.

Cavalieri: Do the translations usually please you?

Brodsky: It’s a very peculiar sensation when you receive the translation of your own poem. On one hand you’re terribly pleased that something you’ve done will interest the English. The initial sentiment is the pleasure. As you start to read it turns very quickly into horror and it’s a tremendously interesting mixture of those two sentiments. There is no name for that in Russian or in English. It’s a highly schizophrenic sensation.

Cavalieri: There isn’t a word for joy and terror.

Brodsky: Jerror.

Cavalieri: Your devotion to the craft as well as to the spirit of poetry is well known. You’re famous for your reverence to the forms, the metrics, the structure. Since you are a man who champions individualism, I have to ask whether you believe there could be some poet’s experience which would not fall within a formalistic structure?

Brodsky: Easily so. I’m not suggesting a strait jacket. I’m just thinking that when the poet resorts to a certain medium, whether it is metric verse or free verse, he should be at least aware of those differences. Poetry is of a very rich past. There’s a great deal of family history to it. For instance when one resorts to free verse, one has to remember that everything prefaced with the epithet “free” means “free from what.” Freedom is not an autonomous condition. It is a determined condition. In physics it’s determined by the statics. In politics it’s conditioned by slavery, and what kind of freedom can you talk of in transcendental terms. Free means not free but liberated, “free from”—free from strict meters, so essentially it’s a reaction to strict meters. Free verse. An individual who just resorts to it has to, in a miniature manner, go through the history of verse in English before liberating himself from it. Other than this you start with a borrowed medium—how should I say this—a medium that is more not yours than are strict meters.

Cavalieri: Do you teach creative writing?

Brodsky: No, I don’t. I teach creative reading. My course at Mt. Holyoke is described as teaching “the subject matter and strategy in lyric poetry”—What’s the poet after; How’s he doing it; What’s he up to?

Cavalieri: Reviewers attribute all sorts of things to you regarding craft…moral, social forces embodied in craft.

Brodsky: All those things are there.

Cavalieri: I am also very interested in your plays and I wonder if you think they’re getting enough notice.

Brodsky: I don’t think they are, but I never expected them to get much.

Cavalieri: “Marbles” was produced just once?

Brodsky: Once or twice here, but all over the place in Europe.

Cavalieri: This reminds me of Howard Nemerov. His dramatic literature is among the best written in English, and it scarcely could get produced. When I read “Marbles” I thought I saw another side to your writing.

Brodsky: It’s actually the same.

Cavalieri: The themes are but you get a little wilder on the stage.

Brodsky: It’s very natural for someone who writes poetry to write plays. A poem, and especially the poem saddled with all those formal hurdles of rhyme and meter, is essentially a form of dialogue. Every monologue is a form of a dialogue because of the voices in it. What is “To be or not to be” but a dialogue. It’s a question and answer. It’s dialectical form, and, small wonder that a poet one day gets to write plays.

Cavalieri: Do you like the theater?

Brodsky: To read but not to go to. Often it’s been an embarrassment.

Cavalieri: You start with an instinctive knowledge of the elements of theater—the containment of the prisoners within a cell (“Marbles”).

Brodsky: The poet in a poem is a stage designer, a director, the characters, the body instructor, etcetera. Take for instance “Home Burial” by Robert Frost. It’s a perfect little drama. It’s also a ballet piece. Even Alfred Hitchcock would like it. There’s a banister which plays a substantial role.

Cavalieri: And we should mention the compression of action of stage. The poem itself is compression of space. The word “Marbles” brings forth many meanings—the colloquialism, the game, the actual statues on stage, all those. What was the word in Russian which carried all those nuances?

Brodsky: The same. Marbles. But it carries less nuance in Russian than in English.

Cavalieri: You have in your poetry humor, irony, wryness. But in theater you do some high jinks. I think it’s much more spirited and you have a chance to break free a little bit more.

Brodsky: Possibly but I don’t think I’m freer in prose than in a poem.

Cavalieri: When you heard that you won the Nobel Prize for Literature that must have been quite a moment for you.

Brodsky: It was funny. I was in the company of John Le Carré in a restaurant in London and a friend ran in with the news.

Cavalieri: Your acceptance speech is one of the finest essays you have ever written. I thought it must have been a pleasure to be able to write that—to be given the opportunity—the chance to say everything that you stand for. It might even have been easy for you to write, because you had this one opportunity to say everything you believe and to tell who you are. What do you think is the one thing which resonates from that speech?

Brodsky: I don’t really know what does. I would advise to a writer to prepare it beforehand for when it happens, when you are awarded the Nobel Prize, you have only a month to write it and all of a sudden you don’t know what to say and you’re under the gun. I remember I was rushing to write it and it was darn difficult. I was never more nervous than then.

Cavalieri: So you think all writers should write an acceptance speech for the Nobel prize just to have on hand?

Brodsky: Yes, just in case.

Cavalieri: Well it isn’t a bad idea to have a credo.

Brodsky: To begin with.

Cavalieri: Even if no one wants it.

Brodsky: You can use it for yourself.

Cavalieri: Are you pleased with the acceptance speech?

Brodsky: Yes I’m pleased with several points.

Cavalieri: You delivered it in Russian.

Brodsky: At the last moment. As I entered the room I made up my mind. I had two versions of it, the Russian and the English.

Cavalieri: And at the last moment you felt more comfortable with the Russian. It was then published in The New Republic. We should reprint that one.

Brodsky: That would be nice because it’s a good speech.

Cavalieri: What it says is that poetry is the only thing that counts.

Brodsky: Perhaps the most valuable remark made there is that there are two or three modes of cognition available to our species: analysis, intuition, and the one which was available to the biblical prophets—revelation. The virtue of poetry is that in the process of composition, you combine all three, if you’re lucky. At least you combine two: analysis and intuition—a synthesis. The net result may be revelatory. If you take a rough look at the globe and who inhabits it. . . in the West we have the emphasis on the Russian now, on “reason.” A premium is being put on it. And the East has reflexiveness and intuition. A poet, by default, is the healthiest possible specimen—a fusion of those two.

Cavalieri: Do you know Václav Havel?

Brodsky: No, I’ve seen him twice.

Cavalieri: Did you speak?

Brodsky: No. It took three quarters of a century for the Czech Declaration of Independence to wind up in the right hands.

Cavalieri: Have you received an invitation to return to your native land?

Brodsky: No I have not. Who cares?

Cavalieri: You haven’t been back since ‘72. Last summer I concentrated on Russian history. But somewhere I stopped taking notes on current affairs simply from fatigue. You must feel that way.

Brodsky: For the first time I’m somewhat proud for the country I was born in. It finds itself in a tremendous predicament. Nobody knows what to do. Nobody knows how to live. Nobody knows what steps to take and, yet, for the first time in its long history, it doesn’t act radically facing this confusion. In a sense that confusion reflects the human predicament par excellence, simply because nobody knows how to live. All forms of social and individual organization, like the political system, are simply ways to shield oneself and the nation from that confusion. And for the moment they don’t shield themselves . . . their faces, Thomas Hardy once said the recipe for good poetry, I paraphrase badly here, “One should exact the full look at the worst” and that’s what takes place right now in Russia so maybe the results will be attractive. I’m not terribly hopeful here because there are 300 million people. No matter what you do, there are no happy solutions for that amount of people. One should be cognizant of that. if I were at the helm, near the radio, near the mic, that’s what I’d tell people. It’s not going to be glorious for everybody. Freedom is no picnic. It’s a great deal of responsibility, a great deal of choices and a human being is bound to make some wrong choices sooner or later. So it’s going to be quite difficult for quite a number of people. The entire nation, at this point, needs something like vocational training because lots of people have been put in jobs wrong for them. They relied on the state—on the paternalistic structure. There is terrific inertia from always relying on somebody and not taking individual responsibility.

Cavalieri: How will the Russian poet reflect this?

Brodsky: I don’t think we can say. Art depends on history or social reality. It’s a Marxist idea, or Aristotelian I think, that Art reflects life. Art has its own dynamics…its own history…its own velocity…its own incomprehensible target. In a way it’s like a runaway train upon which society boards or doesn’t board. And when it boards, it doesn’t know which direction it’ll go. The train started a long time before. Literature (poetry) is older than any existing political system, any system of the government or any social organization. A song was there before any story. And so basically it evolves, develops, and continues along its own lines sometimes overlapping with the history of the state or the society or the reality of society—sometimes not. One shouldn’t subordinate Art to life. Art is different from life in that it doesn’t resort to repetition and to the clichés, whereas life always resorts to clichés in spite of itself because it always has to start from scratch.

Cavalieri: One remark you’ve made about the Augustan era, the Roman time on earth, is that the only record we have of human sensibilities is from the poets.

Brodsky: Yes I think the poets gave us quite a lot more than anything else, any other record.

Cavalieri: What do you think the future will know about us from what we say?

Brodsky: It will know pretty little about ourselves. It will judge us by what literature we leave.

Cavalieri: By what literature remains.

Brodsky: A millennium hence…I don’t know if people will still exist but if they’re interested in the twentieth century they’ll read the books written in the twentieth century.

Cavalieri: You’ve taught at the University of Michigan. You’ve been a Visiting Professor at Queens College, Smith College, Columbia University, and Cambridge. You’ve been awarded honorary Doctorate degrees from Williams College and Yale University.

Brodsky: And some other places … The University of Rochester, also from Oxford, England among others. We should just mention those—not that I’m shaking my medals.

Cavalieri: At each time do you make a speech?

Brodsky: Regretfully, yes.

Cavalieri: Should they be collected in a book?

Brodsky: Well, no.

Cavalieri: Does Joseph Brodsky have any poetry that is not published?

Brodsky: Plenty.

Cavalieri: Is there anyone who’d reject a poem?

Brodsky: Yes, that’s healthy. Nothing changes that way.

Cavalieri: How do you write your poems? Do your poems gather themselves? Do you walk along collecting images until the time to release?

Brodsky: I don’t deliberately or knowingly collect things. The poem always starts with the first line, or a line anyway, and from that you go. It’s something like a hum to which you try to fit the line and then it proceeds that way.

Cavalieri: Mystics say the very beginning of the human species came through sound, the vibration of sound.

Brodsky: That’s nice of them.

Cavalieri: With the poet as well. With you the vibration is first?

Brodsky: Some tune…some tune which has oddly enough some psychological weight, a diminution and you try to fit something into that. The only organic thing that is pertinent to poetry, is like the way you live. You exist and gradually you arrive at a certain tune in your head. The lines develop like wrinkles, like grey hair. They are wrinkles in a sense, especially with what goes into composing…That gives you wrinkles! It’s in a sense the work of time upon the man. It chisels you or disfigures you or makes your skin parched.

Cavalieri: So it’s eroding you and you carry it around?

Brodsky: You do with sentences what time has done to you.

Cavalieri: In the formation of it, are you carrying parts of the stanzas around with you also?

Brodsky: Of course you do, yes.

Cavalieri: And the mechanics…You use longhand first?

Brodsky: Yes, I don’t have a computer. Then I type with one finger. Computers have no use to me.

Cavalieri: Which finger?

Brodsky: Index finger, right hand.

Cavalieri: I saw a poem of yours in The New Yorker last January and I wondered how many poems you get published a year in periodicals.

Brodsky: It varies. For the last year I published about ten.

Cavalieri: Ten new poems in one year. That’s quite a bit.

Brodsky. Yes if you’re lucky. I spent half the year in Ireland and published several poems in The Times Literary Supplement.

Cavalieri: It is said that when you were in a work camp at the time of T. S. Eliot’s death you were able to write your verse to him in twenty-four hours.

Brodsky: Two or three days, yes.

Cavalieri: So you are extremely focused but he also meant a lot to you. That helps.

Brodsky: It did. Also, extraordinarily, under the circumstances, I had a form or shape for that poem. I borrowed from W.H. Auden’s poem “In Memory of Yeats.” I made some changes. I made the first part a slightly different rhyme scheme.

Cavalieri: And you learned English by translating poetry?

Brodsky: By reading it and translating it.

Cavalieri: Line by line by line. How do you think your English is now?

Brodsky: I don’t know. Sometimes even I am satisfied but often I don’t know what to say. I am at a loss.

Cavalieri: Don’t you think we are in any language?

Brodsky: With a mongrel like me it’s perhaps more frequent.

Cavalieri: Do you think and dream in both languages?

Brodsky: People think in thoughts and dream in dreams. They collate these in language. When we grow up we become fluent in this and for that reason we believe that we think in languages.

Cavalieri: Do you ever use material from your dreams?

Brodsky: Frequently. Several times I composed poems when I just woke up. W.H. Auden suggested to keep a pad with a pencil to jot a few things, but mine came out as jibberish.

Cavalieri: Dreams are not always useful except for the feeling load.

Brodsky: The subconscious is a source but a composition is a highly rational enterprise in many ways. You may think of the dream as inspiration but then you type it down and then you begin to correct it. You replace the words. It is an invasion of the reasoning. Poetry is an incurably semantic art and you can’t really help it. You have to make sense. That’s what distinguishes it from other arts…from all other arts.

Cavalieri: You call it the highest point of human locution.

Brodsky: That’s what it is.

Originally published in Volume 10:4, Fall 2009. Grateful acknowledgment to Grace Cavalieri and Forest Woods Media Productions’ “The Poet and the Poem” for permission to print this interview.

Grace Cavalieri's newest publication is What the Psychic Said (Goss Publications, 2020). She has twenty books and chapbooks of poetry in print, and has had 26 plays produced on American stages. She founded and still produces "The Poet and the Poem," a series for public radio celebrating 40 years on-air, now from the Library of Congress.. She received the 2013 George Garrett Award from The Associate Writing Programs. To read more by this author: Grace Cavalieri: Winter 2001; Introduction to "The Bunny and the Crocodile" Issue: Spring 2004; Grace Cavalieri on Roland Flint: Memorial Issue; Grace Cavalieri: Whitman Issue; Grace Cavalieri: Wartime Issue; Grace Cavalieri: Evolving City Issue; Grace Cavalieri: Split This Rock Issue; Grace Cavalieri on Ann Darr: Forebears Issue; Grace Cavalieri on "The Poet & The Poem": Literary Organizations Issue.