First Books IV

Volume 16:2, Spring 2015

Old Maps

Old Maps

Rostov-on-Don, Russia

The river’s the same, curving

gentle and infinite from right

to left across the frame.

And the street grid sketched out

in an age of absolutes,

it’s still there—no one

would dream of changing it.

There’s still a square

in the old town center,

and the cathedral’s

ancient head has been fitted

with a new gold cap.

But factories have filled in

fields beyond the rails,

and the hippodrome

has shifted shape—if

you believe the maps—

from oval to rectangle.

What used to be the town

next door is now Our Town.

Soon Engels Street

will go back to being

Garden Street, I guess;

and Kirov’s bust

(its nameplate comically

misspelled) will be leaving

the park. But they’ll keep

the column that marks

the War, clumsy metal fins

still weighing down

its gilt star. A changeable

wind will still moan down

the streets—sharp-

tongued, implacable—

blowing the seasons

right out of town.

The Cow

The road from Samarkand

slices blue-black and bored

through the salt-veined desert,

past cotton fields bleached

copper green and white,

past mulberries massed

in dusty ranks like soldiers

of the Great Khan. Leaving

town, we thread our way

through busloads of women

and children bound for those fields,

a ”voluntary” Sunday

picking cotton. It’s November:

clear and cold. We woke

in pre-dawn darkness—the stars

of Ulug Beg wheeling

about the astringent heavens—

dressed ourselves in silence,

fingers thick with chill.

Snorting, bucking, the bus

complains its way forward,

exhaling little puffs

of air perfumed with lemon

disinfectant. We day-

dream caravans of hard-

mouthed camels, salve imagined

saddle sores, brush

the coruscating sand

from flesh etched by desert

winds. Cross-pollinating

cultures—Mongol faces

girding Russian churches,

a verb meaning the ground

reddens with blood, the harem

of the last Bukhara emir

“rescued” by Red Army

regulars (they tell us

the ladies went willingly)—

the desert pays no heed,

puzzling only now

and then at the asphalt

ribbons unfurling among

its oases. Here, in the careless

way of deserts and seas,

it casts up a peril:

groan. Shudder. Halt.

Throaty Uzbek vowels:

Flat tire. Please to walk out.

We stumble onto sculpted

sand, follow the sun

as it creeps cautiously

along the ridge, fingers

the horns of a solitary

cow: head tipped back,

legs collapsed beneath,

eyes run wild in sudden,

staggering intimation

of what it means to be

mortal. Been dead some time,

opines a man, surveying

the carcass with a practiced

air. He spits, satisfied,

as if he’s just divined

some mystery. The crowd

breaks into twos and threes,

some wandering up the nearest

slope, some clumping close

to where the driver, grunting,

wrestles a tire to the axle.

Back on the bus, we rummage

for water, snacks, guidebooks

among our day-glo packs,

bags stuffed with prayer rugs,

embroidered hats, suzani.

My neighbor settles a sweater

about her shoulders to nap.

The bus follows the road,

the road follows the sand,

the sand runs unchanging

to Bukhara, looped and laced

by a veil of frailest green:

too frail to sanctify

a dead cow kneeling in dust,

bemused stars—nothing—

reflected in her eyes.

City of Bells

How can it matter in what tongue I

Am misunderstood by whomever I meet….

Marina Tsvetaeva

The songs of my life collect in trams, smelling

of cabbage and stale smoke and yesterday’s

night out. Their melodies orbit the city,

resonate in half-lives—murmurs, grunts,

the thin whine of excuse—cacophony

of a cockeyed city where hammers ring

in resurrected belfries and motors whir

in the Savior’s Tower to synchronize the chimes.

Nothing harrows the wounded soul like music

that takes it unaware: click and trill

of English overheard along Arbat,

careless peal of long-tongueless bells,

swirling cry of a blue-headed crow

that falls and rises like a heartbeat. I know

exactly what you mean, Marina: it doesn’t

matter where I’m altogether lonely.

Here in your beloved city, autumn

frost incises the leaves: season for pickling

mushrooms, for rowanberry jam. For regrets.

Unlike yours, my exile’s voluntary—

what I call home is neither here nor there.

I drift from hand to hand, tongue to tongue,

turning my ear to the one disfigured note,

the too-regular breath, the broken spell.

My lover’s gone, Marina: his words scatter

like birch leaves in the snow. Now he lives

with an ordinary woman. He’s turned his back

on the gods with their nimble-fingered fluting,

spits fthip-fthip-fthip to keep evil at bay.

No one now will pause to recall the rhymes

of his life or the sound of his singing:

drone of a fly on the face of dank earth.

Kingdom of Heaven

Novodevichy Convent, Moscow, sixteenth century

i.

At thirteen, I learned to be a woman:

to limn my skin with lead, like snow,

to brush my brows with antimony,

shape and shade of a sable’s tail.

To rouge my cheeks with beets until

they gleamed like poppies, pull back

my hair so tight I feared I’d faint:

not one single strand could show.

To dilate my pupils with stinging

drops so my eyes would catch the light

just like a falcon’s. I was lucky:

a man saw I was beautiful—

saw I was strong. But he himself

was weak: he died before our wedding.

ii.

Now I pass my days embroidering faces,

studding the halos of saints with pearls.

Fishbone, feather stitch, chain and tuck:

I work their flesh in peach-tongued silk.

iii.

Sometimes in dreams I walk a path

where gold-leaved birches rustle and nod

against an autumn sky. Mushrooms

cluster at the roots of trees, poppies

spill their seed on the fields, I sniff—listen—

my hair, my body now unbound. The path

is peopled with creatures: beneath dry,

dusky skin, the earth stirs, whispers

the language of our feet. In this dream,

my fur glows richer than the sable’s.

I am flying with the falcon.

I am snowing perfect pearls.

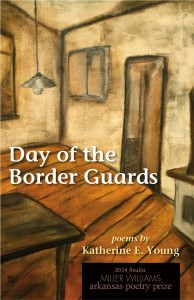

Credit: Young, Katherine. Day of the Border Guards. Copyright 2014 by the University of Arkansas Press. Reproduced with the permission of the University of Arkansas Press.

The University of Arkansas Press was founded in 1980 as the book publishing division of the University of Arkansas. A member of the Association of American University Presses, it has as its central and continuing mission the publication of books that serve both the broader academic community and Arkansas and the region. For almost a quarter of a century, the annual Miller Williams Poetry Series has published some of the country’s best new poetry.

Katherine E. Young is the author of Day of the Border Guards (University of Arkansas, 2014), a finalist for the Miller Williams Arkansas Poetry Prize, and two chapbooks: Van Gogh in Moscow (Pudding House Press, 2008), and Gentling the Bones (Finishing Line Press, 2007). Her poems have appeared in Prairie Schooner, The Iowa Review, and Subtropics. Young is also the translator of Farewell, Aylis by Azerbaijani political prisoner Akram Aylisli (Academic Studies Press, 2018), named one of 2018's "Eleven Groundbreaking Works" by Words Without Borders; as well as Blue Birds and Red Horses (Toad Press, 2018), and Two Poems (Artist's Proof Editions, 2014), both by Inna Kabysh. Her translations of Russian-language authors have appeared in Asymptote, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Penguin Book of Russian Poetry, Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine, and 100 Poems About Moscow: An Anthology, winner of the 2017 Books of Russia Award in Poetry; several of her translations have been made into short films. Young was named a 2015 Hawthornden Fellow (Scotland), a 2017 National Endowment for the Arts translation fellow, and a 2020 Arlington (VA) Individual Artist Grant awardee. From 2016 - 2018 she served as the inaugural Poet Laureate for Arlington, Virginia http://katherine-young-poet.com/ To read more by this author: Evolving City Issue, and Museum Issue