Volume 15:4, Fall 2014

A Splendid Wake Issue

1. Vision

Of all the issues of the journal Callaloo, the most storied and perhaps well known is Issue 23. This is the Callaloo issue devoted to the life and art of Black Arts Movement icon, Larry Neal. If the uninformed reader or observer would like to understand the life and work of Neal, they would be wise to track down this copy of the storied journal.

Of all the issues of the journal Callaloo, the most storied and perhaps well known is Issue 23. This is the Callaloo issue devoted to the life and art of Black Arts Movement icon, Larry Neal. If the uninformed reader or observer would like to understand the life and work of Neal, they would be wise to track down this copy of the storied journal.

Callaloo #23 appears in Winter 1985, four years after the untimely death of Neal, and twenty years after Neal, Askia Touré, and the late Amiri Baraka, launched the Black Arts Movement (BAM), along with so many other Black artists, writers, musicians and activists. It was a time of monumental political challenge and change; yet Neal is sometimes lost in discussions of the period and the aftermath.

Neal, poet, playwright, and critic, was one of the hot writers of BAM. He edited the seminal anthology of the period, Black Fire, along with Amiri Baraka, and he forever took his place in the center of the movement but yet, on his own, in his space, for his unique belief in art.

To a certain degree, an entire issue devoted to a BAM icon like Larry Neal seems a bit out of place for Callaloo. Over the years, a certain distance has developed between the publication and BAM for reasons many believe are complex and elusive. Yet, in Callaloo #23, there is no distance; there is a desire to engage and inform the world of Larry Neal and his vision. This coming together might also be possible because it is Neal, who was a man and artist not devoid of controversy but one who was able to speak to a wide array of individuals and communities.

In Callaloo #23, Larry Neals art takes center stage and Neal takes center stage. Roy Lewis, the celebrated photojournalist who also has strong ties to BAM, provides a photo of Neal on the front cover and the giants of African-American literature offer their words and analysis of Neals work. Amiri Barakas essay The Wailer, a tribute to Neal, is here, as is commentary from Ishmael Reed, Stephen Henderson, and Eleanor Traylor, among those of note.

Charles Rowell, the long-time editor of Callaloo, has an interview with Neal and that is one reason the issue is fulfilling. The interview challenges many of the misconceptions presented over the years regarding BAM and Neal.

Among many things, Neal told Rowell of his appreciation for Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Welsh legend, Dylan Thomas, who Neal praises for his strange imagery. For a BAM artist to speak coherently of embracing these writers outside their space is quite amazing considering the times. But Neal says much in the interview even analyzing Countee Cullen and Claude McKay as writing Keatsian literature despite his appreciation for their work.

Neal also tells Rowell of the real importance of BAM, of its ability to develop for African-Americans their own aesthetics: Its impossible for Afro-Americans to develop any kind of unique literature, if they can merely imitate the imagistic clusters of Anglo-Americans. They must, according to Neal, perceive their own reality and perceive the symbols and images and metaphors implicit in that reality.

Neal proposed to Rowell an African-American aesthetic rooted in the blues and jazz, imagery that links to Black dance, speech and history. He calls this an iconography I have lived, one he can claim as his own. In a sense, Neals vision was seeking greater possibilities for not just Black writers but all writers and for that matter, all artists, because it was daring to suggest new forms, new approaches that were developed in the West, but were not Western. This is one of the core foundations of BAM.

Stephen Henderson, the Howard University literary critic, said Neal was a writer who held contradictory elements in a state of high tension. Neal, according to Henderson, saw art as a tool of political change but also viewed it as vehicle of transcendence. This vision likely clashed with some hardcore BAM personalities who likely became artists in the 1960s only because of BAMs political outlook. Neal was, as Ishmael Reed notes, complex, an artist and individual who saw possibilities in unlikely scenarios. This included the identification of African-American form in art and a new paradigm overall for Black writers and writers who respected that idiom.

2. Sacrifice

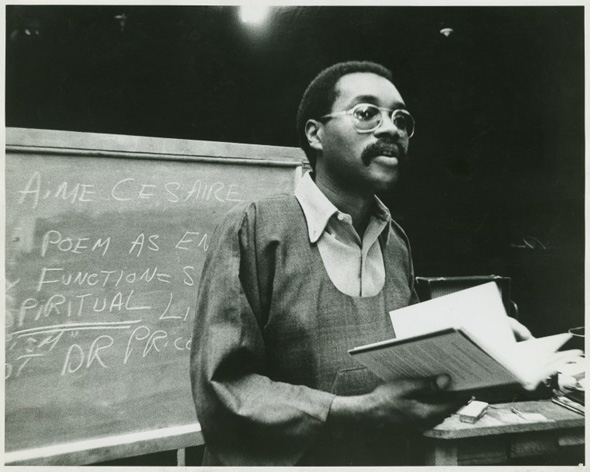

Larry Neal, photo courtesy of Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library

When Larry Neal assumed the post as Director of the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities, he noted: What is life without art and ideas? Government can help take art to people. Look what happened in the 30s with the WPA. WPA is, of course, the Works Progress Administration, that government-safe haven for many artists of the Depression era. Neal, channeling WPA, speaks to his connection to art.

Neal served the city of Washington DC as Director of the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities from 1976 to 1979. All indications are that Neal was a dedicated civil servant who was able to engage the public with his ideals if only for a short time, and to manage challenges including his own incompatibility with directing a bureaucracy.

As for the art part, Neal was already part of the city long before 1976 in a real way. He made his unofficial debut in the city in 1969 when a portion of his manifesto on BAM was reprinted in the Washington Post obviously because of the critical success of the anthology Black Fire:

It is a profound ethical sense that makes the Black artist question a society in which art is one thing and the actions of men another. The Black Arts Movement believes that your ethics and your aesthetics are one.

Even though Neals statement is grounded in BAM ideals, his statement has universal appeal. This likely goes back to Neals attachment to diverse ideas as demonstrated in Callaloo #23.

There is ample evidence that once again, as seems to be the case with the arts in the United States, that support for art during Larry Neals time running the commission was scattered and often weak. Initiatives such as a $600,000 grant from the federal governments CETA program were a rarity. The usual scenario had the small agency stumbling along, seeking to stay alive and independent, and various arts organizations complaining as well and struggling to deliver Neals vision of government taking art to the people.

This was probably best revealed in August 1977 when the federal government slashed the arts commission budget by $700,000 much to the disappointment of Neal and then City Councilmember Marion Barry, who also championed the arts at the time. There were numerous moments where the public wanted more support for the arts but the support simply wasnt there.

But the commission had moments. In November 1977, the commission sponsored Craft Arts: A Washington Exposition. The program, presented at public libraries in the city, and at museums such as the Textile Museum, allowed 410 DC artists to showcase their art work in four days of exhibits at various locations. The commission awarded nearly $200,000 in grants in 1979 (with complaints), including $10,000 for a film on political prisoners that likely didnt please Washingtons bureaucrats.

Even with the challenges, Neal was ambitious and futuristic. We want to initiate programs, Neal said in March 1979, develop programs and get technical apparatus together so the funds are not drained in the arts groups. This statement is consistent with Neals desire to support not just big organizations but individual artists who had something unique to express, like Neal.

Larry Neal, a clever and cutting edge writer, wanted to support writers especially. Myra Sklarew, who worked with Neal, described the experience as a particular pleasure and said Neal was imaginative in his role as Director, and concerned with the needs of the writer.

Overall, Larry Neal was (and is) a writer. He was no bureaucrat, though he served with zeal and a positive outlook for the city and its people. He left his government work to return to writing in early 1979 because, as it would seem, this is what he really was at heart. By the summer of 1979, he was living in Harlem, and his play, The Glorious Monster in the Bell of a Horn, was in production and reviewed by the Amsterdam News. Neal continued to write and produce high art until his sudden death in 1981. He made a personal sacrifice to the city of Washington DC. Artists like to do their art or work; they do not want to be bureaucrats. However, Neal made the sacrifice that others would after him. The annual Larry Neal Writers Awards still maintained by the Commission are a testament to his giving. His own writings are an even bigger testament.

Sources/References

Callaloo Issue #23, Charles Rowell, ed., John Hopkins University Press, Winter 1985.

Larry Neal and Michael Schwartz, eds. Visions of a Liberated Future: Black Arts Movement Writings, Thunder Mouth Press, 1989.

Larry Neal, Hoodoo Hollering Bebop Ghosts, Howard University Press, 1974

Brian Gilmore is a poet, writer, and columnist with the Progressive Media Project. He is the author of three collections of poetry, elvis presley is alive and well and living in harlem (Third World Press, 1993), Jungle Nights and Soda Fountain Rags (Karibu Books, 2001), and his latest, We Didn't Know Any Gangsters (Cherry Castle, 2014). He has published in The Progressive, The Nation, The Washington Post, Book Forum, The Baltimore Sun, and Jubilat. He currently teaches at the Michigan State University College of Law. He divides his time between Michigan and his beloved birthplace, Washington, DC. To read more by this author: Brian Gilmore, Spring 2001; Brian Gilmore's Introduction to The "Woodshed" Issue, Fall 2001; Brian Gilmore on Waring Cuney: Memorial Issue; Brian Gilmore: DC Places Issue; Brian Gilmore: Evolving City Issue; Brian Gilmore: Split This Rock Issue; Brian Gilmore: Audio Issue; Brian Gilmore: It's Your Mug Anniversary Issue; Brian Gilmore on Drum & Spear Bookstore: Literary Organizations Issue; Brian Gilmore: Langston Hughes Tribute Issue.

Larry Neal taught at City College of New York, Wesleyan University, and Yale University, and co-founded the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School with Amiri Baraka. He is the author of two books of poems, Black Boogaloo (1969) and Hoodoo Hollerin' Bebop Ghosts (1974), as well as several plays, including The Glorious Monster in the Bell of the Horn (1979) and In an Upstate Motel (1980). Neal was co-editor, with Baraka, of the journal Liberator and the landmark anthology Black Fire: An Anthology of Afro-American Writing (1968). A collection of his essays and other work, Visions of a Liberated Future, was published posthumously in 1989. Neal lived in DC from 1976 to 1979. He died of a heart attack at age 43 in 1981.